| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/27/2024 Occurred: 9/26/1998 |

Page Views: 1627 | |

| Topics: #Arizona #GrandCanyon #HavasuCanyon #HavasuCreek #Havasupai #Indianreservation #Supai | |||

| 1998 camping trip to Havasu Canyon with Michael. Directions, photos and text. | |||

When we think of Paradise on Earth, the image that usually comes to mind is Tahiti, prior to the arrival of Captain Cook and his band of cultural elitists. Before 1750, Tahiti was a land where people obtained their food and created their shelter in joy; children laughed and ran barefoot amongst the fruit-laden trees; there was no pollution, no European diseases like smallpox or polio, and no sense of inferiority to anyone else. Today, while Tahiti still retains its excellent climate, it has become a tourist Mecca whose high-rise luxury hotels are not paradise to those of us who like nature and the outdoors, and where Tahiti's once-proud and carefree people serve as chambermaids and porters to the privileged who come to its shores for a few days of vacation. The Paradise that was Tahiti is long gone.

Is it possible that Paradise can actually exist on Earth? In 1998? Better yet, could a pocket of Paradise actually be found within the continental United States, actually within reach of those who need it most?

Amazingly, the answer is "yes!"

Near the western end of the Grand Canyon is a side canyon called Havasu. The water that runs through it all year long is called Havasu Creek, and the people who live there are known as the Havasupai, which means, in their language, People of the Blue-Green Water.

They live in Paradise.

I've rafted Grand Canyon several times, and each time we've made Havasu Creek a must-stop feature of the trip. It's fantasy-like blue-green color, the countless pools and cascades, the whimsical rock formations that line the canyon, all combine to make it an unreal place, the place of dreams. Typically, we'd hike five miles from the Colorado River to Beaver Falls, the last waterfall before Havasu Creek joins the Colorado. I knew the Havasupai lived further up the creek; but it wasn't until I was surfing the ‘Net in 1998 that I discovered tourists were welcomed by the Havasupai…if you could get there. I immediately made plans for my then-partner, Michael, and me to go. After all, why postpone a visit to Paradise?

Directions

To get to Havasu Canyon, you first have to get to Flagstaff (the nearest commercial airport). Since we live in Arizona, my partner Michael and I simply drove there. You continue down I-40 to Seligman, AZ, origin point of the famous Route 66. Gasoline in Seligman is a bit pricey, but you'll want to fill up—you have a long drive to go, and there are no further gas stations—Paradise is not just off the Interstate.

You continue west on Route 66, past the Grand Canyon Caverns (a lonely but interesting attraction that has survived in spite of the demotion of Route 66 to side road). This is the last civilization you'll see; there is a motel and a campground, and many people use this place to spend a last night before making the final leg of the journey. We did not, however. We continued on, as you must do, to Tribal Road 18, where we headed north some 60 miles to the very end of the road. This is a place called Hualapai Hilltop, and it is the last pavement you'll see, until you return from Paradise.

(That's the route we took. Now, with Microsoft Streets and Trips, I find we could have saved quite over 60 miles by cutting across on US 180 to Valle, then on Willaha County Road to Supai Rd, to Hualapai Hilltop, and so on, as shown below.)

It is possible to take a helicopter into Havasu Canyon, but Michael and I didn't know that. We knew the usual way to go is to hike, and that's what we were materially prepared to do (though perhaps not physically prepared). We had everything we needed (and perhaps a bit more) in our backpacks; we locked the car, parked among perhaps thirty others, at the hilltop, and began our descent into Paradise.

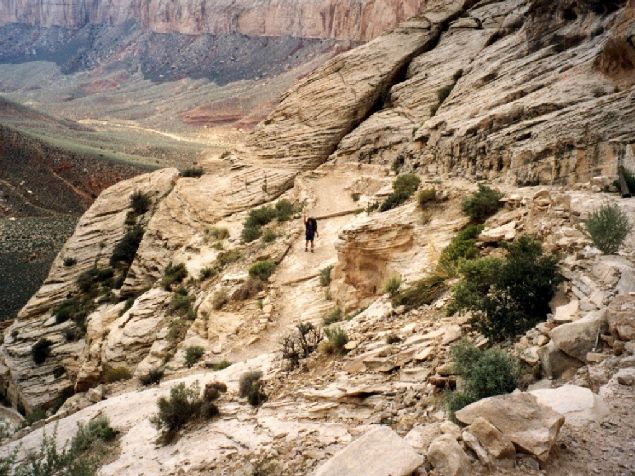

It is eight miles to the village, named Supai. The first mile is a steep descent, dropping more than a thousand feet. But, the view is spectacular! This is not Havasu Canyon; it is a dry canyon (Havasu joins it later) that has, nevertheless, seen a great deal of water. The evidence is everywhere: In the hollows carved into the canyon walls, in the rounded stones lying about, in the gravel floor. Once at the bottom, the trail is easy to walk, and you do not walk it alone. While it is not a crowded trail, neither is it lonely. We did encounter others leaving, and were even passed once or twice by parties on horseback. (The droppings of the horses are another reason why the trail is easy to follow.)

We had gotten a rather late start. Dawn is the recommended time, and we didn't arrive at Hualapai Hilltop until about 3:30 PM. Almost everyone we passed looked at us, then at their watches, then back at us—which was a bit unnerving. Everyone who passed said hello, and most did it with German accents. I knew from past experience that Grand Canyon is a favorite haunt of German tourists; but it was a bit of a surprise that they knew about Havasu Canyon.

A Lady And A Dog

Although Havasu Canyon is not part of Grand Canyon National Park (it is owned by the Havasupai people), it is nevertheless part of the geology of Grand Canyon and looks much the same—especially within the side canyons. Even the descending-tone warble of the Canyon Wren can be heard there.

We are not speedy hikers and were further slowed by my picture-taking, and Michael's identifying every tree, flower, and plant we passed. By the time we reached the five-mile marker, it was already getting dark and we had three miles to go before we reached the village, and two miles further to the campground where we had reservations. Our feet hurt, our backs hurt, and we were beginning to wonder whether it was really Paradise we were hiking to, or the "other place." I was in favor of finding an out-of-the-way spot to pitch our tent, but Michael was intent on reaching the village.

"It's against the rules to camp anywhere but the campground," he pointed out. "These people are gracious enough to accept us as guests; we shouldn't impose on them in any way."

"Wouldn't it be a greater imposition for them to find our dead bodies and have to bury us?" I grumbled; but we continued.

By the time we had gone another half mile, full, moonless, night had fallen. The walls of the canyon were black, featureless; the sky was an irregularly-shaped cutout through which glowed the most incredibly brilliant stars. We sat, gasping, sore, sipping water, when the sounds of an approaching animal caused us to freeze. A dark, dog-like shadow induced Michael and I to start an argument over whether it was a dog or a coyote. Before we could come to a conclusion, more footsteps crunched; our flashlights focused on a woman holding a pillow in one hand and a purse in the other.

"How far is it to the top?" she asked, her German accent slightly slurred.

"It's quite a ways," I said. "More than five miles. Are you heading back to the hilltop?"

"Ja," she replied. "Those people have too many rules."

Michael shook his head. "I don't think you can make it. You don't have a flashlight?"

"I can make it," she replied, fiercely, and continued on her way, stumbling along the gravel trail.

"Well, at least you have your dog," I called after her, thinking that the dog could lead the way; and, besides, how lost could you get in a canyon, even in the dark?

"What dog?" she replied, her voice fading into the darkness. "I don't have a dog." And she was gone.

Arrival

Some miles later we came to a stream crossing the path, and had to switch from our hiking shoes to our Tevas. The cool water felt wonderful on our feet. Shortly afterwards Havasu Canyon joined the one we'd been hiking, with Havasu Creek merrily splashing its way through the darkness. It was surer of its way than we were, though. Trying to follow horses' hoof prints in the glow of our flashlights, we eventually came to the darkened outlines of some buildings. When we cast our beams about, we awakened horses, mules, and dogs; the whinnying, braying and barking in the tomblike night created the most ghastly alarm. Careful, now, to aim our flashlights at the ground, we found it impossible to follow the instructions we'd been given. Where was the Post Office? The Café? The General Store?

Weary beyond belief, I finally convinced Michael that setting up our tent as far out of the way as possible wouldn't create a tribal incident. We found a spot near the creek, assembled the tent, and collapsed gratefully into a sore stupor.

Early in the morning, the sound of hooves roused me and I looked outside to see a man regarding us from atop his horse. I hastily rose to greet him and to apologize. "We got in really late," I said. "We couldn't find the trail…"

"It's just part of the wilderness experience," he smiled. "When it's time to leave, if you want pack animals to carrying your stuff, look me up. You don't have to arrange it with the Tourist Office—I can make you a deal."

At the moment, the thought of hiking back was more than I could bear. So I got directions to the Tourist Office, where we had to check in, and woke Michael. We reloaded our packs and put them back on; the few hours' sleep we'd gotten hadn't eased our soreness by much.

The Tourist Office wasn't yet opened, so we first had breakfast in the Tribal Café, an unimposing building that nevertheless boasted air conditioning and modern, fast-food restaurant-style molded plywood booths. Frankly, my expectations were not high; but breakfast was wonderful—scrambled eggs, bacon and hash browns for me; the same with sausage instead of bacon for Michael.

At the tourist office, I was relieved to find that they had received our pre-payment. The Havasupai do not take personal checks; credit cards and money orders only, please. I had sent a money order but had not received any confirmation. In arranging the trip, I had spoken with two different people, each of whom had quoted me different prices. Now, it turned out, we had overpaid. But that was fine with me; I asked for an additional night's reservation and we were lucky enough to get it. (This being late September, the place was not filled to capacity with tourists.) I knew we would need the extra day just to be able to walk out. I had already figured we'd take our friend up on his offer to mule-lift the packs.

Supai, the village, has been home to the Havasupai since about A. D. 1300. They apparently recognized it immediately upon finding it, as being a Paradise; moreover, although most historians do not believe the Native Americans navigated the Grand Canyon, the Havasupai know that they (and all humanity) originated and came from there. They only moved out onto the upper plains in the winter, when food in the canyon became scarce. There, in the cold winter months, they could hunt enough game to provide the year's bulk of meat. Come February or so, they would return to their Paradise for the remainder of the year, living on the crops they planted and making the artful baskets which their neighbors so admired.

As has happened in the case of so many other Paradises, white civilization intruded and threatened to destroy the whole thing. A Congressional document, quoted in the Havasupai Museum located in the Tourist Office, states that the Grand Canyon is too beautiful to be left to the "unappreciative Indians," and should be taken from them so that civilized people could enjoy it. Consequently the Havasupai were confined to a mere 518 acres of land, crammed into the Paradise that couldn't support them year ‘round. It wasn't until 1975 that President Gerald Ford signed a bill that returned some of their traditional lands, another 185,000 acres in the high country. But the damage was done; the population had dropped, old skills had been lost and many of them were irrelevant anyway: Who in North America expects to spend the winter hunting for meat to be eaten the rest of the year? This is, after all, the age of Hamburger Helper.

With other tribes turning to the lucrative casino business to get back some of what the American Government had taken from them, the Havasupai decided on a different approach. The Tribal Council voted to never allow a road to be built to their isolated paradise. They knew the canyon could support a certain number of visitors a year and they built facilities for exactly that many: the campground, and a small lodge. Tourism is now their primary source of income. Although they are a quiet people, they are friendly and kind and make ideal hosts. And, unlike the Tahitians maids and porters, the Havasupai know they are working for themselves. They are the hosts, not the hired help.

It was still early when we left the Tourist Office and not many people were stirring. The main street is the trail, well-traveled; a road of soft, red, dust. We hiked past the school, a little church, and several homes. One had a travel trailer in the yard, presumably serving as extra rooms; I wondered how it had gotten down there, since there are no roads. Past there, the trail descended, never far from Havasu Creek, which in the daylight did indeed glow its iridescent blue-green color. Past 120-foot Navajo Falls (named for a former chief of the Havasupai, not the tribe), past 150-foot Havasu Falls, which were so spectacular that we paused in spite of our aching muscles; into the campground and into the first available campsite, where we again set up the tent, unpacked our packs, and collapsed into our sleeping bags in spite of the fact that it was ten o'clock in the morning of our first day in Paradise.

Exploring

Hours later we awoke. Neither Michael nor I carry watches (they refuse to keep any kind of accuracy for me, and on Michael they have been known to actually run backwards), so we didn't know what time it was—a requirement for Paradise, if you think about it. We staggered to our feet and put on swim trunks, intent on making our way to Havasu Falls. The trail to it went uphill and Michael and I traversed it in the peculiar gait of two who had walked ten miles with fully-loaded packs the night before. (The locals refer to this as the "Supai Shuffle.")

The usual words—"spectacular," "awesome," and the like—used to describe waterfalls do not apply to Havasu Falls. That's because the falls themselves are only part of the story. The setting for the falls is what makes them truly special. Over the past several million years, Havasu Creek has carved out a natural amphitheater for itself, 150 feet high and maybe six hundred feet wide and deep. The two main cascades are perfectly centered in this arena, so that one's attention is naturally drawn to them (as if it wouldn't be, anyway). The waters, bright in the sunlight, fall into a shadowed pool past brown ribbons of aged travertine, calcium deposits built up by the water on the rock walls. The wind and mist billow out from the center of the pool, catching the sun's rays and cooling people parched after the dry hike here.

After the main pool, the water pours from smaller pool to smaller pool; there are a dozen cascades and little pools, perfect for the person who needs a Jacuzzi after hiking, or the feeling of privacy; and the pools continue downstream, providing each tourist or resident with his or her own private space, made to order: In the mists of the falls, in the quiet sunlight, large for a big group or small for an individual or couple. In addition, metaphysically speaking, the water is charged with psychic energy. It is said that wishes made while soaking in it, come true.

I, of course, wished that my feet and shoulders would stop hurting. And they certainly did feel somewhat better, afterward!

Upstream from Havasu Falls, closer to the village, is Navajo Falls. At about 120 feet, they are third highest of the canyon's four falls; and, seen from the trail, pretty but not spectacular. Don't miss the side trail, though! At the bottom you'll find a private, hidden haven; the four main cascades hidden amongst the cottonwood trees and, for real privacy, one can slip behind the waterfall, to feel the quiet moist air against one's skin, to experience the odd contrast of still air and mist so close to the thunderous crash of the water falling just a few feet away.

The stream runs through the center of the campground, with campsites located on either side. There is one main collection of privies at the south end of the campground, with one small privy located at the center and one at the northern end. They are primitive, one-time porta-johns turned into pit toilets. None of them had toilet paper and they did not all have undamaged seats; they are not for the squeamish. On the other hand, they beat having to dig a latrine, which is usually the case when camping so far from the highway.

We found that quite a few of the campsites had been vandalized. This was a puzzle to me, until I remembered the remark made by our German lady with the pillow: "They have too many rules." We had been given a list of rules at the tourist office; I didn't find anything on the list intrusive at all. But there was one item on it I suspected some might find oppressive: It is against Tribal law for alcohol to be consumed on Havasupai land. Picture some of the campers, college-aged types perhaps, who get sloshed and are told they must leave or, at least, are reminded that drinking is prohibited. I can easily imagine some of these folks getting rowdy and trashing the place in revenge.

In fact, the man running the campground knew about the lady with the pillow. "Oh, yes," he said. "She was wandering around the whole campsite last night, drunk as a skunk. I wondered what finally became of her." He assured us that she was not likely to come to harm in the canyon, and that in the morning one of the pack trains would find her if she was still there and return her to the rim.

The dog walking with her, that she disclaimed, was one of the village dogs. There are dozens of them, of every shape and size, from the cutest fuzzy puppies to the oldest, battle-scarred veterans. Most of them wear collars, even flea collars; but they seem to roam the canyon at will. The males each adopt a campsite and will guard it from other dogs, but not from that night's campers. In exchange they expect, and usually get, a few leftovers. These dogs are so sweet-tempered that it seemed to me perfectly likely, that one of them had taken it upon himself to make sure the German lady remained safe during her hazardous, drunken night hike from the canyon.

Camp

"Our" dog was a back Lab-derived mutt with numerous scars and a red collar. Like all the others we saw, he was respectful, never begging for food but making sure we were aware, during dinner time, that he was there, by occasionally thumping his tail against the ground in happy companionship. The technique worked; not only did he get to lick our plates and pans, but when we were lightening our packs before the dreaded return trip we gave him the contents of every can we had: deviled ham, chicken salad, Dinty Moore Chicken and Dumplings. We left him one happy dog.

Cleaning up was not a bothersome chore…and not just because Michael volunteered to do it. (I cooked.)

Although there was no dishwasher, there was, nevertheless, the most breathtakingly beautiful kitchen sink either of us had ever seen!

About a half mile north of our campsite is Moony Falls. This is the tallest of the four, at 190 feet. The pool at the base of Moony Falls is said to be the preferred swimming spot, but I don't see how. The trail to the base of the Falls is an almost vertical pastiche of switchbacks, chains to be used as handrails, and even a section through which one must slide through a travertine tube. Going down is bad; climbing back up is even worse. But the pool is beautiful. I suspect it is more inviting in July and August, when the temperature approaches 100°F, and swimmers appreciate the shade…and find the grueling climb afterwards to not be too high a price to pay.

Another reason to descend the Moony Falls trail is that, about six miles past Moony Falls is the last of the Havasu waterfalls, Beaver Falls. Although Michael and I didn't make it there this time, I had been there before while on rafting trips. Beaver Falls is small, only about forty feet high; but that means you can play in it safely, not just in the pools around it. And, yes, there are the travertine terraces and myriad pools. In addition, Beaver Falls is remote enough for real privacy; I have never been there when anyone was present other than my own party.

The Green Room

There is another thing special about Beaver Falls: The Green Room.

Not many people know about the Green Room. I heard about it from a Colorado River boatman, who then refused to take me there. It's supposed to be very dangerous to visit, and a mythology has built up around the danger that, when I finally got there myself and found it wasn't such a big deal after all, the two young boatmen with me refused to see it for themselves, even though I assured them it was safe and worth the trip.

The Green Room is under Beaver Falls. To get there, you have to get behind Beaver Falls, which isn't easy, because there are travertine curtains on each side of the falling water. You have to stand on underwater protrusions and hurl yourself through the falling water with enough force to punch through, or the waterfall will simply kick you out. You can't see through the waterfall, so you don't know what's there—you have to take it on faith that the area you are diving toward is, in fact, free of obstructions.

It is. Once behind the curtain of water, you are in a still eddy, the thunder of the waterfall inches away. But that was the easy part. You're not in the Green Room yet.

To get there, you have to dive underwater—keeping away from the force of the waterfall, which still wants to kick you away from its backside—and locate a large hole about five feet beneath the surface. You'll need enough breath to swim into this hole, even though only a yawning blackness lies before you. After about eight feet, the tunnel curves upwards; after another four or five feet, you break the surface. But you have to be very careful: You'll be in a small cave, and there's a stalactite hanging directly over your head. The biggest danger is that you'll come up too fast and puncture your head on the stalactite. I always rise slowly, with one hand covering the top of my head.

Now, once your ears break the surface, comes the magic. This whole time, you've heard the thunder of the waterfall, transmitted through the water to your ears. The moment your ears break the surface, however, you experience a sudden and complete silence.

The Green Room gets its name from the color of the light as it passes through the blue-green waters. Inside the little cave there is clean air, and hanging ferns, but nothing else. There is room for two people to share the experience, but no more. Time seems to stand still as you hang, suspended, in this place so completely hidden from everything you just left: Time, sound, sunlight, the smell of cottonwood, the call of the Canyon Wren. Once you have been in the Green Room, it is always with you. You can always find it inside. It is a little paradise hidden with Paradise.

Return Home

You can't stay there forever, though…neither can you stay in Havasu Canyon forever, unless you are fortunate enough to actually be a Havasupai person, yourself. I am not, so, eventually, it came time to go.

It appeared that meant hiking back out the canyon. But, as the days had passed and Michael and I felt not much less sore than we had originally, we began to dread that hike out. Fortunately, by now we knew we had other choices. We could ride out—except that Michael and I each exceed the 200 pound weight limit for horses. We could send our stuff out by pack animal, and hike…but my feet were still blistered. And so, we decided on the final choice (other than finding a couple of single Havasupai women and marrying them): taking the helicopter out.

The helicopter, run by AirWest with the authorization of the Havasupai, doesn't fly every day but it did fly this day. There's a clipboard put out at the Tourist Office for people to sign and gain a place in line. By the time we got to the village, staggering under the weight of our packs and the two-mile uphill walk from the campground, everyone who wanted to go had already signed up. So our names were the very last on the list.

Villagers have first priority seating, and the chopper can only hold four passengers at a time. So, we wound up spending the afternoon in the shade of the outdoor seating area of the Tribal Café, waiting our turn and passing the time by chatting with other tourists and watching the pack mules delivering goods to the local store (and eating some of them!). There were a few Havasupai hanging out there, too; but they are not a talkative people and we'd already been warned not to start a conversation with them—allow them to start one, if they wished. We did speak with one woman who was there with her two very young children. She kind of didn't count as Havasupai, however, since she was born in China. Since her husband was German, we never did quite figure out how she got to live there. She was happy about it, however; she loved that her kids could run barefoot all though the village without her having to worry about them. For her, that was much like her childhood in China—Paradise.

Eventually, it came our turn. Because of weight restrictions, Sally, the woman in charge of loading and unloading the helicopter (and she did the actual unloading, too, slinging bags of horse feed like they were soap bubbles), asked me to fly ahead of Michael, which I did. And what a ride! The scenery was more spectacular, if possible, from the air than it had been on foot. Of course, it was a little invalidating that the distance covered in over six hours on painful feet was a matter of about ten minutes in the helicopter. But I didn't care. And when, a few minutes after dropping me off, the helicopter returned with Michael, we had to agree: We finally, definitively, knew what Paradise was.

Paradise is not having to walk back.