| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/26/2024 Posted: 3/27/2007 Updated: 9/16/2017 |

Page Views: 3083 | |

| Topics: #DigitalPhotography | |||

| When scanning or saving digital photos, you'll want to know how much resolution you need. | |||

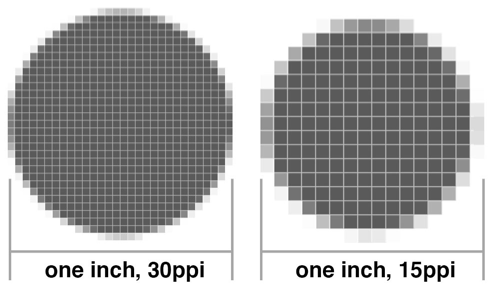

Resolution refers to the number of pixels, or dots, into which your photo is broken. The more pixels, the smaller they are; the fewer, the larger. If you have large pixels, the resulting computer file will be smaller, because you will have fewer pixels to store. However, if you try to enlarge your photo, it will get blurry because bigger pixels mean fewer pixels, and that means less information to go around.

So you can go the other way, and ask for a high-resolution scan. Now the pixels are tiny, so there are a great many of them—millions of them, in fact. Now you can get big enlargements made, but the files will be bigger.

A fair compromise is to get the equivalent of what you get with a 5.1 megapixel (or so) digital camera. With that over five million pixels, you can get excellent 8 x 10" (or larger) enlargements made of your image, should you ever wish to do so.

Your scanner will talk about DPI (dots per inch) or PPI (pixels per inch). The two acronyms are synonymous, because Dots = Pixels. DPI is used more with paper; PPI used more with computer monitors; but they are the same. Do note, though, that printer dots are smaller than monitor dots; so a resolution that looks great on your screen, might not print out as an enlargement, as clearly as you expected.

The basic formula is (of course):

which can also be expressed as

or

Inches, in this case, is the size of the larger of the original image or the largest enlargement you'd like to print. Your printer will tell you what size dots it uses; modern photo printers typically boast resolution of well over a thousand dots per inch. The absolute minimum for a clear photo, in my opinion (and this is subject to opinion) is 800 PPI. (Many people argue that 300 PPI is adequate. And it's true, a lot depends on the clarity of the original photo: If it started out fuzzy, more dots on the printer won't clear it up.)

So, let's say you are starting out with a 4 x 6" photo that you would like to scan, then enlarge to 8 x 10". The target is what you first need to calculate; the scanned result will need to be

That's what is often called "5.1 megapixels". That's what good quality digital cameras offered two or three years ago, meaning that they were intended to produce photos that would make clear 8" x 10" enlargements, if called upon to do so.

Therefore, regardless of the size of the original image you are scanning—print, slide or negative—if you want to print an 8" x 10" enlargement from it, you need to scan at a high enough resolution to produce (approximately) 5.1 megapixels. More than that won't help (or hurt), but fewer than that will impact the clarity of the finished product.

So you'll need to scan the 4 x 6" original at about

Now, we've bypassed the issue of resolution, because the number of pixels is a product of the resolution times the size of the image being scanned. The resolution would have to be a lot higher for a tiny negative than for a 4 x 6" print, to produce the same number of pixels. But you can use the following formula to determine what the scanning resolution should be somewhere between 450 and 500 pixels per inch. (Exactly what choices are available to you depends on your scanner and its software.)

If you are going to have your negatives and slides professionally scanned, you can generally just tell the scanning people that you want 5.1 megapixel results and they'll figure it out for you. If not, however, you can refer to this table for common sizes:

| File Size | PPI |

|---|---|

| 35mm | 2000 |

| 126 | 2200 |

| 127 | 1600 |

| 120/620 Square | 1100 |

| 120/620 Rectangular | 800 |

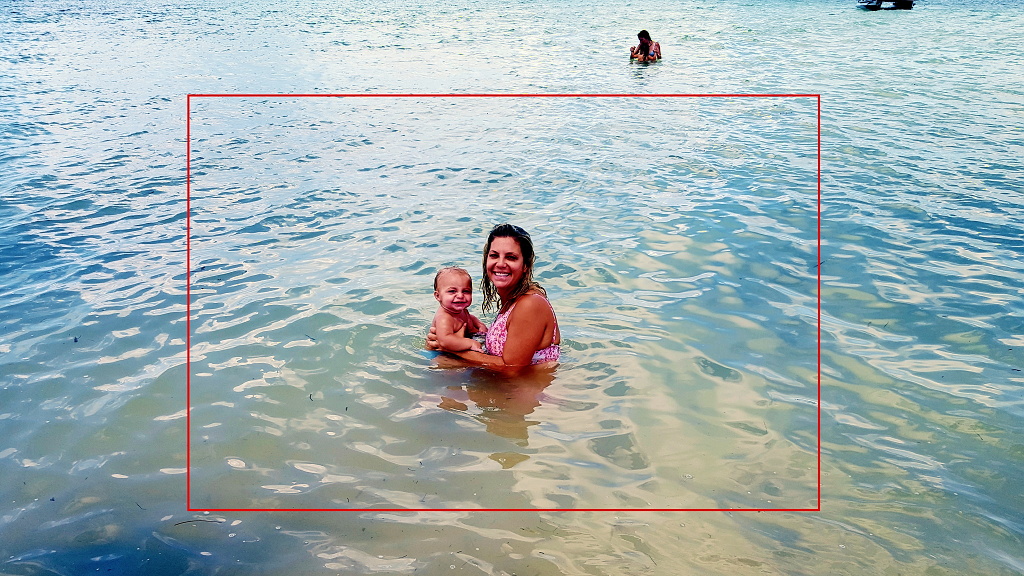

If you plan to make really large prints, perhaps of a beautiful slide you took with your expensive film camera, don't hesitate to ask for a higher resolution—perhaps as much as 12 megapixels or more, the density produced by today's state-of-the-art digital cameras. Also, if you expect to do some heavy cropping—removing much of the outer parts of the picture to "zoom in" on a distant subject, for example—you'll obviously need to start out with a higher resolution.

The next question that will come up, should you decide to have your slides and negatives professionally scanned, is: Should you request "raw" scans, or retouched scans? The former is a lot cheaper, but you may be disappointed with the result if image manipulation isn't something you're comfortable with. While the scanning company will be automatically removing most blemishes from color slides and negatives (Digital ICE doesn't work on black and white), and doing some color correction, I have found that on older slides and negatives there is still work to be done, to correct for uneven color shifting, for example, or unusually severe damage from scratches or fungus. This work can be tedious, though I have found only I can do it to my satisfaction!

Another common "fix" that can be made, either by the lab or by you, is removing "red eye". As you surely know, when flash pictures are taken in dim light, the flash illuminates the interior of your subjects' eyes, causing them to photograph a bright, Satanic red. The problem is so common, and the fix so simple (change the red disk to black, while retaining any white highlight that might be present) that just about every photo-fixing program includes a feature to handle it easily. If you ask your lab to do it, it generally doesn't add a lot over the general cost of retouching.

Cropping is something you'll just about have to do yourself, unless you have no artistic sensibility at all. At issue is the fact that every camera has a fixed area into which the picture is composed. (APS cameras had three, but the principle is the same.) As you frame your shot, you do your best to work with that area: You center your subject, or perhaps balance it with a tree or building or interesting cloud. Another reason for cropping is remove distracting or unrelated items from the scene.

In the days of paper prints and enlargements, another compromise had to be made in order to fit your photo onto the desired size paper. For example, if you enlarge a 35mm negative so that the image fits the width of an 8" x 10" print, the sides of the image will spill off the edge. On the other hand, if you fit the long dimension onto the 10" of paper, the image will not reach to the 8" edges. This compromise was handled automatically by the printer; but if you make your own enlargements it's something you'll have to keep in mind.

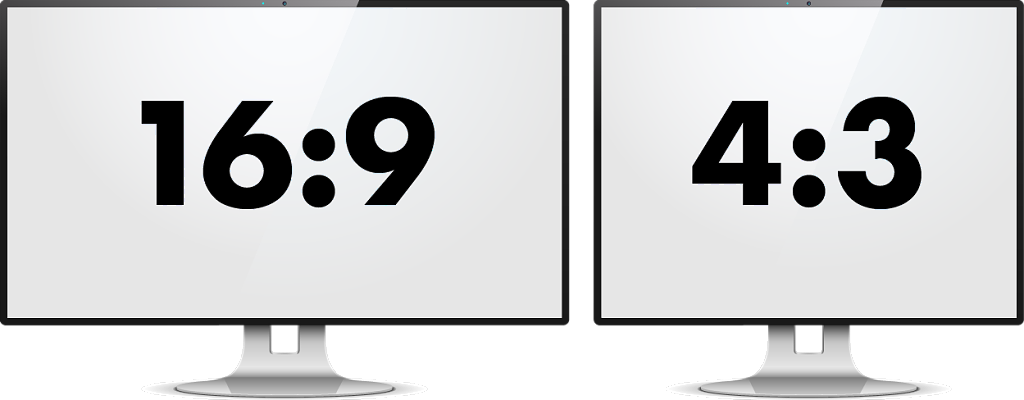

And, besides, your computer monitor will probably be your photo display of choice into the future. A standard-sized monitor uses a 4:3 ratio (the width of the screen is four units to the height's three units) which will force cropping of nearly all your photos if you want them to fit perfectly. Besides, the "widescreen" ratio of 16:9 is becoming popular; it's quite likely that within the next ten years, that's what you'll be viewing your photos on. Before you can make all your photos fill the screen, you don't even have to decide, now, which screen!

Fortunately, they don't have to. You can now crop your photos to show your subject to its best effect, and let your monitor supply borders as needed. The Windows Slide Show, provided in every version since Windows XP, as well present in most modern photo editing apps, built into any folder that contains photos, will handle the display job automatically. All you have to worry about is the actual, original cropping.

While cropping, you should also make sure your photo is properly aligned. It's very difficult to take a picture with the camera perfectly upright; but if you don't, the resulting image will need to be rotated a degree or two. It's an easy thing to do and all photo editing software helps you do it. Just don't forget—it does need to be done.

Apart from color correcting, most photos benefit from adjusting the brightness, contrast, and even color saturation (how bright/gray the colors should be). These tweaks can be made to improve your photos. We'll examine some of these techniques in a future entry.