| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/23/2024 Occurred: 5/31/2009 |

Page Views: 1614 | |

| Topics: #McCarthy #Alaska #Rafting #KennicottRiver #NizinaRiver #Travel #Photography | |||

| All about the rafting trip in Alaska with Michael and Frank. | |||

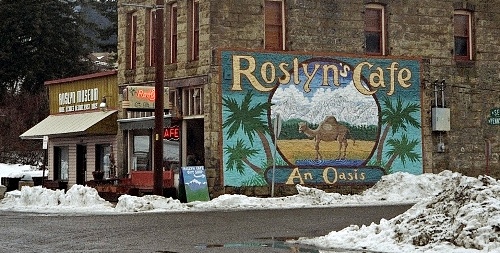

Some years ago, I visited Cicely, Alaska, the fictional town featured in the 1990s TV series Northern Exposure. I was able to do this without actually going to Alaska, because "Cicely" was actually a side street in the town of Roslyn, Washington. The TV series, however, had renewed my interest in visiting Alaska, which had become a state in 1959 when I was in 3rd grade. My visit to "Cicely" only strengthened my desire to visit the 49th state someday. Now I was here, not only in Alaska but over 300 miles from Anchorage in the little town of McCarthy, which could have served as the template for fictional Cicely. Remote, quaint, set amid pristine wilderness and populated by quirky yet friendly characters, I couldn't help but draw comparisons even as my husband, Michael, and our friend, Frank, and I prepared to go rafting down the Nizina River.

The email we'd each received as our confirmation of having prepaid for the rafting trip instructed us to meet the river guides at 9 AM…we thought. None of us had actually printed the instructions. Actually, I thought it was 9:30 am. But Frank remembered 9, and it seemed prudent to go with the earliest time. So he had set his phone alarm to go off at 7 AM.

Michael took a shower; Frank might have, too; I don't know. There were three shower rooms to choose from. However, I still felt clean from the sauna the night before; besides, I'd be spending the day on a river. So I just threw on the clothes I had planned for rafting (SmartWool socks, polypropylene long johns, a long-sleeved gym shirt, gym shorts—no cotton!—and my new Alaska baseball cap) and scrambled a bunch of eggs for breakfast. Michael came in from the shower and fried up a pound of bacon; and with the addition of some not-from-concentrate orange juice, we had a proper meal.

Frank's friend Brad's Kennicott River Lodge, where we were staying, is on the "outskirts" of McCarthy. That means it is accessible by automobile. The road doesn't actually go all the way into town. A five minute walk brought us from the lodge to the end of the road and a footbridge that crosses the Kennicott River.

At the far end of the bridge, a van was waiting to take us into town. Actually, the van was waiting for anyone who might want to go into town. It turned out we were early; the rafting company wasn't expecting us until 10 am.

Which was okay; that meant we could make a brief tour of McCarthy (which was all it would require) before heading for the rafting company's headquarters.

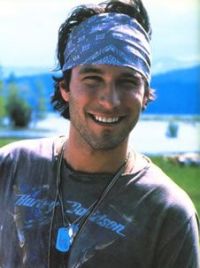

Without a specific destination in mind, the van delivered us to the van headquarters, which is also the air travel headquarters. After rafting we would be returning via a bush plane hired through the air travel people. Steve, the controller, was not himself a pilot but waxed enthusiastically about the history and geography of McCarthy and the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. He was very knowledgeable and quite handsome; so in my mind he became the real-life model for Northern Exposure's Chris Stevens.

Since we had time before rafting, Chris—I mean, Steve—suggested we wander by the McCarthy Mercantile, where we could get some coffee and homemade Danish. On the way I snapped a few photos.

The Mercantile did, indeed offer coffee and pastries. Frank and I were each pouring ourselves a cup when it occurred to me to ask the young lady who ran the place (I imagined her as Northern Exposure's Shelley Tambo) if they took credit cards. They did not. And I had no cash with me. Frank had enough change with him for one cup. So he and I shared.

We then sat at a table on the Mercantile's wooden porch, enjoying the sun and the increasingly perfect weather, as various locals went in and came out with purchases: coffee, muffins, banana nut bread. Each also took the time to stop and chat with us. They seemed genuinely friendly and open, completely disarming.

Our instructions to the raft company were to go to the "power plant". So we walked toward the river. The power plant building was not in operation and had changed hands more than once; it still bore the previous name Wrangell-St. Elias Alpine Guides although it is now home to Copper Oar Alaska Adventure Travel. The co-owner (with her husband) Gaia Marrs (think Northern Exposure's Maggie O'Connell—pretty, strong, competent, independent), met us in the yard where she was helping to carry an inflated raft. She explained our luck in having chosen to raft today: Normally, the first trip of the season is made on June 1st. But this year, the glaciers were melting early and the water had risen to a level that made rafting possible a day or so early.

However, there was a problem. Although I had pre-paid for the rafting, and received confirmation emails, it turned out they hadn't actually put through the charges. While on the trip I could check my balance but not my statement, so I assumed the charges had been put through and spent more money than I actually had. So, between my two cards, I had to get the rafting paid for. Which I did, but now I was worried about having enough money for my return trip—I intended to pay for the gas, for example.

Because it was the first trip of the year, in addition to Michael, Frank and I, there would be two new guides-in-training, plus Gaia, plus the lead boatman Jules Hanna. That made, as Gaia pointed out twice, an excellent guide-to-client ratio of 4-to-3.

We then added to our outfits. Over the SmartWool socks, polypro underwear and non-cotton shirts and shorts (wet cotton rapidly steals heat from the body and so is never worn on a cold river), we were given wet suit tops, waterproof pants, and waterproof boots. Oh, and a lifejacket. At this point we looked more like the Creature From The Black Lagoon than river rafters. But the glacial river water is barely above freezing and we wouldn't want to spend the day shivering.

We clomped to the edge of the river where the rafts were awaiting us.

At the Kennicott River's edge, looking north we could see the great glacier whose melt feeds the river. This is the same mile-high glacier we could see from the lodge's main building. You can also see, in the photo below, the footbridge that links the road and the town.

Because the water levels change on a daily, or even hourly, basis this time of year, Jules used his paddle to determine whether the water was deep enough in the near "braid" of the river for our raft, or whether we would need to carry it across the river bar to the next braid over. It turned out it was deep enough, a fact that Jules determined by virtue of the near-freezing water pouring over the top of his boot.

I had purchased a clear plastic dry bag for my Canon G10 that featured an optically clear lens through which the camera's lens could take photos…in other words, a waterproof bag to protect my camera on the river, that would allow me to take pictures without exposing the camera to danger. It cost me $50, compared to the $168 of Canon's official underwater case. It did protect the camera, and it did allow me to take photos on the river. On the other hand, the outer lens had a tendency to slip to the side and partially obscure the view. When I got home, I had a devil of a time cropping the pictures so that the outer lens edges wouldn't show.

Frank's solution was simpler. His entirecamera was waterproof. Like mine, it shoots video as well as still photos. Frank used it constantly. I'm not certain he ever saw the river through his own eyes; it was mostly through his viewfinder.

We brought paddles so we passengers could paddle if we wanted, but we didn't really want to. Frank and I wanted to take pictures and Michael wanted to enjoy the scenery. That was okay, as the raft was already outfitted with an oar frame. So Jules began rowing, and we were on our way.

Although the rivers we would travel occasionally boast class IV rapids, that's when the water is higher. Today's trip was a mild class II at best, which was okay because as cold as the water was, none of us had a special desire to get wet. Besides, we'd all been on rougher rivers and for us, it was more about the wilderness experience and the scenery and camaraderie than the thrills.

After a few miles on the Kennicott, we reached its confluence with the larger Nizina river. The water was now wider and deeper and flowing ever faster. Moreover, metaphysically speaking, Michael and I both sensed an energy shift as we joined the new river.

We stopped for lunch across from a small ice fall that clung to the steep bank. Michael took pictures of wildflowers—he knew the names of all of them, of course—while the guides prepared lunch.

For the most part Michael, Frank and I wandered separately as we waited for lunch. There was so much room that we could spread out, still be in sight of each other and the river guides, yet experience a mild taste of the expansive isolation possible in this huge place.

In addition to the flowers, we found the river rocks themselves to be fascinating. Each was completely different from its neighbors, having been brought here by millennia of glacial scraping across the northern thousand miles of Alaska.

By now the day had actually grown warm. I was surprised at how strongly the sun's rays felt this far north. Given that we were breaking here for over an hour, I decided to do as the guides and Frank had done and remove the upper part of my river outfit. Yes, I was shirtless in Alaska!

Lunch was fantastic—built around homemade bread from the Mercantile and homemade salmon salad. I don't particularly like most fish and am not the biggest fan of salmon; but this stuff was delicious. Or maybe it was the sunshine and incredibly fresh air stoking our appetites.

There was also dessert: Homemade chocolate cake and carrot cake, as well as fresh fruit slices. All washed down with lemonade, ice tea or water.

We all ate too much.

And then we were back in the raft for the second leg of our journey.

As he had promised, Jules let me row for a few minutes. It had been over ten years since I had last worked an oar frame, and I must admit it was more of an effort than I remembered. Still, I have now rowed in Alaska…and not many people can make that claim!

There were two other rafts accompanying us. One was similar to ours; Gaia and a new guide named Collin took turns rowing it. Both were learning the river for future trips: Collin because he's new to this river, and Gaia because the river changes every season and she, too, would be leading trips out here eventually.

The third raft was special, a "catamaraft", two inflated tubes connected by an oar frame. When Frank and I last rafted the Upper Salt with just two other passengers, we took one raft to do it. But the Upper Salt isn't near as remote as the Nizina. So, for safety's sake, all river runs here include at least two rafts. That way, no matter what happens to one, the other can go for help if need be. On today's trip, the catamaraft was manned by another new guide, a young man named Danny.

As we traveled, different mountains and ranges came into view, replacing others. Frankly, they looked much the same to me—spectacularly beautiful, but I was unable to memorize the shape of one versus another over the course of a single trip. In fact, it seemed to me that the area of Washington State in which Roslyn is located, actually does look a lot like this part of Alaska.

We made a mid-afternoon stop for a pee break. Before taking off again, we posed for an "our boat" photo.

The banks of the river began to rise as we proceeded downstream. The glaciers have been retreating since the 1980s or so; the further downstream we went, the more time the river had had to cut through and thus the deeper into the earth it went. At higher water levels I could easily imagine class IV rapids at the various constrictions formed by rock slides.

A highlight of the trip was Nizina Gorge, where the banks became solid rock and rose to an impressive height.

Finally the gorge opened up and we came to its confluence with the even larger Chitina River. There was a river bar between the two, a long one, where we beached the boats. The rafting trip was over, here in the middle of a literal nowhere (the magic word that at once says "no where" and "now here"). Michael, Frank and I removed our borrowed river wear; I was handed my wallet and shoes, which had been stored in a dry bag. Because I couldn't get to my shorts yet I put the wallet down on a pile that also included my polypropylene undershirt and a fleece hoodie I hadn't needed, after all. That freed me to wriggle out of the waterproof boots and pants so I could put on my shoes.

Then a small yellow airplane came out of nowhere (again, from no where to now here) and rolled on big balloon tires to a stop on the river bar. That was to be our ride back to McCarthy (because, as the river guide joke goes, rivers don't flow in a circle). He would take the three of us first, then return for the crew and the rafts—which would require at least two more trips.

The pilot, Kelly, wanted to load the back seats first, and wanted the two lightest passengers in back. Frank is obviously the lightest of the three of us and Kelly decided I was next. So Frank got in, and I handed him my pile of stuff so I could climb in next to him. Then Kelly rolled the front passenger seat back and Michael boarded. Kelly was no lightweight either—he sort of reminded me of Red, one of Cicely's bush pilots in Northern Exposure.

We taxied down the bar, turned around, got up speed and made it into the air with all the grace of a booby taking off. We gained altitude rapidly though, and I was amazed to see how small the rafts we'd left behind looked.

The rivers' confluence was much easier to understand seeing it from above.

We more or less retraced our route, though of course Kelly was able to shortcut sections of river that made 'S' curves we'd had to follow in the rafts. It was fun to recognize places we'd seen, or stopped at, on the ground. (In the center of the photo below, you can see the ice fall across from where we had lunch.)

But this wasn't simply a return; it was billed as a "flightseeing trip" so we kept going, flying over McCarthy toward the mountains and the glaciers that supplied the water we'd been rafting on all day.

One of the things that had surprised me greatly was how silty the water was. I had expected glacial meltwater to be crystal clear and delicious. I have no idea how it tastes because it was so loaded with silt it looked like flowing cement. We'd been warned that, if we fell into the water, our pockets would quickly become so filled with silt that we would be unable to swim.

As glaciers slowly flow downhill they scrape the land beneath them. Although it's all in slow motion, the ice in the glacier tumbles and churns as water would; so the bits of rocks and clay and the stones and boulders get distributed through the ice.

At the melting edge of the glacier, most of the melting occurs to the top layer. Some water flows away; some sublimes in place (changing directly from solid ice to water vapor). Either way the silt remains. So, as we approached the mass of ice, we first flew over a moraine of silt under which was still solid, yet flowing, ice. It looked very much like the surface of the moon. In the photo below, the tiny streaks of white are ice exposed through crevices in the accumulated silt.

Finally we came almost within touching distance of the mile-high river of ice that is Kennicott Glacier.

Frank has been to a glacier, further north and closer to its source, where the ice is a solid, deep blue. At this end of the glacier, however, the effects of decades of weathering show as striations in the surface, darkened by collected silt and windblown dirt.

Before turning back, Kelly treated us to a view of one of the guardian peaks between which the glacier flows.

We then flew over the ghost town of Kennicott, once the site of a major copper smelting plant that serviced a number of nearby mines and is still the location of the world's largest wooden building (towards the bottom of the below picture). From the air it looked like it was composed of toy buildings.

We also flew over the Kennicott River Lodge where we were staying. We could see Brad's new under construction cabin, our cabin, and the main lodge quite easily.

Finally, we flew over the town of McCarthy, just before landing at the field just north of town.

Finally, we were on the ground and the mountains were once again higher than we were. Which is as it should be.

Kelly assisted us out of his plane and we sat to wait for the van to drive us back to the footbridge. That's when I realized I no longer had my wallet.

I remembered putting it on the boat when Frank handed it to me from the dry bag, but couldn't remember if I'd retrieved it afterwards. The only thing that was certain was that I didn't have it now.

Frank suggested that I might have dropped it in the plane. I trotted over to check. As it was when we had boarded, the floor was steeply slanted toward the back. It was easy to see under the seats but if anything had fallen it would have slid backwards; and all I could see behind the seats were black hoses and pipes. No wallet.

Which means I must have left it on, or in, the raft. The guides would find it when they cleaned and deflated the raft preparatory to its being flown out. Indeed, they might well have already found it; but there'd be no way to communicate that to us. However, they knew where we were staying; and I was sure they would call as soon as they were flown back.

The van showed up and we boarded for our trip to the footbridge. I chatted with the driver about Northern Exposure. "So," I asked, "do you guys have a Maurice Minnifield?" He was the character in the show who was the richest man in town, owned almost everything, and, while not evil, had an agenda for turning Cicely into the "New Alaskan Riviera" with casinos and condominiums that he attempted to impose on the other characters.

"I don't think we have anyone here like that," our driver snorted. "Our winter population is only 18."

When we arrived at the footbridge, I suddenly realized there was a mystery. "There must be some other way into McCarthy," I said. "How would you get gasoline to run this van? For that matter, how did you get the van here? And I've seen a couple other vehicles, too."

The driver got out with us. "I'll show you," he said, and we walked out a few yards onto the footbridge. He pointed downriver. "See that other bridge?" he asked. "There's a family in town that owns the property on both sides of the river there. They had that bridge privately built, and a road that crosses it. The road is locked and monitored at both ends. For several hundred dollars a year, they will license a vehicle and one driver to use the road and bridge. A few companies in town have those licenses, and that's how we get our vehicles and supplies in."

"Ah," I said. "So you do have a Maurice Minnifield, after all!"

We were bone tired as we walked back to the Lodge but I made sure to stop at the free telephone installed at the west end of the footbridge to leave a message at Copper Oar to call the Lodge when the crew returned with my wallet.

It was about 5:30 pm when we walked up the driveway into the lodge. Brad wasn't there, but he'd left a note on his door saying he'd be back at 7 and where he intended to lodge the two parties who were to arrive. The three of us decided to take a nap for a couple of hours in our cabin. When we awoke, Brad still wasn't back. So I had no idea if Copper Oar had tried to call about my wallet or not.

Still, there was all that dinner to make. At the store, I had expected to make dinner this night and I planned on beer-battered fish fillets and potatoes with broccoli. Then Frank and Michael said they wanted shrimp, so we got that and some fettuccini and Alfredo sauce, and I put back the potatoes but somehow kept the fillets. Frank wanted scallops added to the fettuccini, but I'm not sure why he bought the four halibut fillets. In any case we now had enough food for three or four meals, and only one night to eat it.

I started to get pans out but soon it was obvious that Frank and Michael were going to make dinner; so I got the hell out of their way! I sat on the porch, enjoying the view; and when the first couple arrived I showed them the lodge, as Brad had shown us the night before: where the outhouse was, and the showers, and their room in the main building.

Brad drove up about the same time as the second party, a family of five (six if you count the yapping dog) from Venezuela who were assigned to the cabin next to ours. Shortly afterwards the massive dinner was ready, and because there was so much food I asked the other guests if they'd care to join us. But the couple had already eaten and the family had promised their kids they'd toast hot dogs over a fire.

I had also invited Jules to come by for dinner. He and Brad are friends anyway and I'd have loved to hear them perform some of their original songs. But there was no sign of Jules and no message yet from Copper Oar about my wallet.

Did I mention the four ears of corn we'd also bought and cooked?

Well, the meal was exquisite but of course we could barely make a dent in it. Frank and Michael are both superb cooks and clearly their working together had produced a result that was greater than the sum of the parts. Even so, the beer-battered fish fillets went to the two dogs Brad was dog-sitting, because he was out of dog food and I was afraid they'd eat the Venezuelans' yapper. Never in the history of the world have two dogs eaten so well. And they got to top it off with fettuccini Alfredo!

Frank, Michael and I had kind of been looking forward to the sauna again, after a day on the river. But when it came down to it, the four of us (Brad had spent the day at a birthday party) were just too tired to bother. So we went to bed.

We would be leaving in the morning. But first, I was going to have to get my wallet from Copper Oar…and, hopefully, they had indeed found it. Otherwise, how would I ever get through airport security to return home?