| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/16/2024 Occurred: 6/15/1972 |

Page Views: 7128 | |

| My six months of fame. | |||

I had always wanted to work at a radio station.

St. Augustine had two radio stations: WFOY, to which everyone listened, and WETH, to which almost no one listened. WFOY was the "easy listening" station; its only real competition for listeners was Jacksonville's WAPE ("The Big Ape!") which played rock 'n' roll. But all the adults in town listened to WFOY.

And so that's where I set my sights.

"Pappy" Schilling didn't own WFOY, though some thought he did. He did co-own it, but his was definitely the voice of the station, doing news and talk through the morning before the station began its music broadcasts in the afternoon. When I showed up on my bicycle one day, he let me in and gave me a tour of the station, even allowing me to stand and watch when he turned on his microphone and spoke. I was probably 16 at the time, and was completely blown away by the glamour—and also by the station's impressive music library.

In the afternoon, Pappy let me pick out records from the library and hand them to him to play. I didn't know most of the titles, but anything there was "safe" for airplay and I began to learn of the existence of a lot of songs I might never otherwise have encountered.

It was Pappy who suggested that I put on a weekly, five-minute "Boy Scout Show" in which I would interview kids in my troop. I had just discovered the song "Java" performed by Al Hirt and loved it. Tommy Wilbur, one of my best friends in Boy Scouts, could play it on the piano. So I made that the show's "theme song", even though playing it took half our allotted five minutes.

The station's primary owner was one Pat Bernard. I only found out that Pat was co-owner years later, when I worked at a title assurance company. When we first met, Pat introduced himself to me as the owner. But he actually shared that distinction with Pappy Schilling.

In the attic of the station were shelves full of antique 78 rpm shellac records. When I told Pappy that I used to have a Victrola and loved the old music it played, he sent me up to the attic to browse. However, while I was there, looking fondly at copies of records I had once owned, Pat threw open the door and growled, "What are you doing up here?"

I began to explain about the Victrola, but Pat wasn't interested. "I saw you smiling at them," he hissed, as if that were a synonym for urinating. "I never want to see you here again." And he stood aside so that I, shaking, could leave ahead of him.

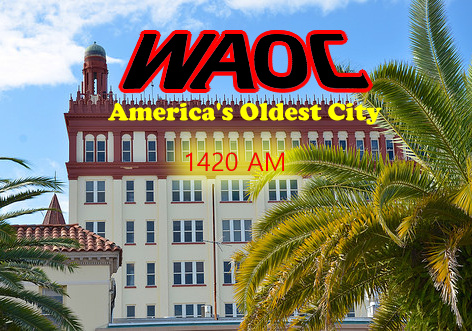

Obviously I would never be able to work at WFOY. So I re-aimed at WAOC, with offices in the Exchange Bank building that dominated the St. Augustine skyline. (Its transmitter was located in the woods west of town.)

WAOC, which seldom had anyone in its offices other than the announcer, was also amenable to entertaining young, curious visitors. And it was announcer Dick Harnage who told me what hoops I would need to go through in order to get my Second Class Radio Operator's License from the FCC so I could apply for a job as announcer at that or any other station.

At 18, I sent for the study materials, went to Jacksonville to take the test, and passed. But then, WAOC wasn't hiring.

Now, however, in 1972, knowing that my job as Palm Coast tour guide wouldn't be lasting much longer, I applied again. And this time…I was hired!

I was walking on air as I made my way into the office on my first day of work. A man from Alabama, Wayne Sims, had recently bought the station and created a new format for it, half rock/pop and half country. This put us in a position to compete with WFOY, or would if people found out we were there. Wayne's wife was secretary and bookkeeper.

Wayne had a very thick Alabama accent that I never suspected from listening to him when he was on the air, because he could also speak "radio"—that sanitized middle-American accent used by announcers accross the country. I waited quietly as he gave the news as it might have sounded on CBS, then clicked off his microphone and turned toward me. "Now," he drawled, "whut kin ah do fer yew??" In all the months I worked there, his on-again, off-again accent always tickled me.

In addition to Wayne, myself and Dick, the other announcer was a fellow who called himself "Tony Ring" (no relation to the race car driver) who bore an uncanny resemblance to the "Herb Tarlick" character on WKRP In Cincinnati, a TV show that would not air for another six years.

On my first day I was shown the basic set-up: Two turntables, a microphone, a mixing board, a couple of reel-to-reel tape recorders, two "cart" recorders for commercials, and another ancient device that recorded some fifty commercials on different tracks of a single, foot-wide strip of magnetic tape.

I was in my element, segueing songs like "One Tin Soldier" into "Whose Garden Was This?" and gleefully playing the occasional "soul song" (such as Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack's classic "Where Is The Love?", knowing that some of our hard-core redneck listeners would pitch a fit when "colored music" was played on the air. (We actually got calls, and that was actually the phrase the callers used—when they were being polite.) Wayne was determined that we not give in to what he called the "KKK element" and I was delighted to cooperate.

I admit I was a boring disc jockey. I loved playing music; I wasn't interested in talking about it. Some people look at a microphone, think "millions of listeners!" and freak out. I looked at the microphone and thought, "lifeless hunk of metal!" and couldn't think of anything interesting to say. Sometimes I might get a visitor and then I could talk to that person and be very cool. But alone…meh.

My State Farm Commercial

We were also expected to create and sell advertisements. Mine were very creative, sometimes too much so. For example, I created an advertisement for Terry Gordy State Farm Insurance, delivered by the deceased, himself, at a séance. These commercials were all done "on spec", meaning the company being advertised hadn't asked for them. Having them on cassette made cold-calling the potential customer a little easier. However, how was I to know that Terry Gordy was a born-again Christian who found the very idea of séances offensive, and spent the next 45 minutes explaining to me exactly which verses of the Bible backed him up on that. And did I know I would be going to hell, and that State Farm had no insurance against that other than my accepting Jesus Christ as my personal savior?

But, actually, most of my ads did sell. My biggest success was for Collies' Li'l Shrimp House, for whom I sang their menu to the tune of "Little Green Apples".

Dick Harnage's commercial production was amazing. Every now and then when he wasn't announcing, he would go into the auxiliary recording studio, open up a phone book, and place a record of pre-recorded commercial background music onto the turntable. These were specialized records purchased by radio stations for local ads. They consisted of background music in various styles: Jazzy, pop, classic, adventure, and so on. Armed with only the information from a company's Yellow Pages ad and the music, he would ad-lib a series of ten or twelve commercials for them, each polished and fitting perfectly to the music. Since the musical pieces were timed at 60 and 30 seconds, they were ready to go when he was done. (He was already friends with all his customers, so his commercials were pre-sold.)

One spot he did, however, was not so well-done. It was for a "big contest" WAOC was putting on. I remember him telling Wayne and me about it. It was "The Great Football Prediction Show Contest". People were supposed to send in postcards to enter. On the appointed day, we would pick one card at random. The person whose card we picked, didn't win—yet—but would "appear" on our weekly Football Prediction Show with our Football Prediction Master, Wayne Sims. If the contestant was able to out-predict Wayne on who would win that weekend's college football games, then he or she would win the contest prize: Driving, absolutely free, a brand-new car from Jack Wilson Chevrolet for one week.

Dick was very excited about it, but it seemed like a pretty lame prize to me.

"Are you kidding?" Dick asked, incredulously. "Do you have any idea how much it costs to rent a car for a week?"

"Do you have any idea what the odds are the winner will have been just about to do that?" I shot back. But the contest was on.

So Dick did a spot for the contest. It was not one of his best. He rambled on and on, with no musical background. And where spots are supposed to be 15, 30 or 60 seconds (we had to log them for the FCC), Dick's was an inconvenient 112 seconds long.

It bothered me every time I ran his spot. It bothered me every time I logged that I had run it. And finally, one afternoon after 5:30 pm (when we went off the air), I decided to do something about it.

I copied Dick's spot on reel-to-reel tape and transcribed exactly what he had said. I then cut the tape into separate strips, one for each sentence. I then made up a script, in which Dick, with some of the sentences from his ramble, and I, seemed to have a conversation:

And so on. I then recorded my lines, spliced Dick's sentences in with mine, and recorded the result back onto the antique commercial machine with an Isaac Hayes musical background. End result: All information presented in exactly 60 seconds.

Now, too late, I had second thoughts. Dick would be at work in the morning and run his spot, only it would present a conversation between us that had never happened. Would he be mad? Hurt? But the damage was done. My mashup had replaced his original, and there were no backups.

When I came in the next day, everyone behaved perfectly normally—including Dick, who was his usual, friendly self. No one said a word about my new, improved version of his spot.

The only reference to it came weeks later. I was in the announcer's booth with the door to the auxiliary recording studio open, as it usually was unless someone was recording in there. Dick and Wayne were working together, replacing a piece of equipment, and chatting as they did so about the other employees, as if I weren't in earshot. "Tony is an idiot," was the sentence from Wayne that got my attention.

"You gonna fire him?" Dick asked.

"Ah don't think Ah'll have to. Ah've heard rumors he's a-lookin' fer work."

"Will you give him a good review?"

"Hell, yeah! Ah'll he'p him pack if Ah have to."

"How's Paul doing?" (And at this, I froze in disbelief that they didn't realize I was just a few feet from them, if out of sight around the jamb of the open door.

"Wahl, he's not most exciting D.J. Ah've ever heard," Wayne admitted, "but he is the absolute best tool user Ah've ever known. Th' way he turned yer contest spot into a winnin' commercial was astoundin'."

Knowing that Wayne put great stock in a person's abilities to work with the tools of his trade meant that this was a great compliment. Like I said, I knew I wasn't a great disc jockey. I bored myself. But what I really enjoyed doing was creating commercials. And knowing that Wayne appreciated and understood the work that went into that, made his words absolutely precious to me. I have clung to them in al the decades since as a sort of validation, and striven to be worthy of them.

Eventually, of course, the contest was held. By the appointed date we had received exactly three entries. The three cards were put into a hat; I was chosen to pick one out, which I did. We called the number and asked for the name on the card. The person on the phone broke into sobs, and cried that her husband had died the week before.

Wayne's wife selected the second card. Its owner wasn't dead, but his wife told us he was in Nova Scotia fishing and couldn't be reached. He'd be so sorry when he got back to find out what he'd missed. When we suggested that she participate in his place, she said, "Oh no. He's the one who shouldn't have gone fishing." Then she added, spitefully, "Or whatever he's really up to."

The third card was submitted by someone whose name I recognized: Sister Patrick Theresa, the nun who'd taught kindergarten to my classmates and every Catholic kid in St. Augustine since. She subsequently appeared on The Great Football Prediction Show, was successful in beating our Football Prediction Master, and used the car to ferry around kindergarteners in the week she had it. So it all turned out well.

With a regular paycheck coming in, and with our friend and roommate John having decided to move out of the trailer in Breezy Brae, Mary and I were able to rent an apartment on the top floor of a converted house within walking distance of work.

The yellow outline shows the part of the house we lived in. We entered via the outside stairs into a long, windowed hallway (formerly a porch). One passed the bathroom and bedroom before reaching the living room. Then a left turn led to the kitchen.

There were two other families living in the house as well. One was a friend of my Mom's from her work, and the other, Tommy, had attended my high school some years before.

I first became conscious of the power of the media on the day that Mary and I had an argument. I don't remember what the argument was about, just that it was some factual thing that neither of us would budge on. I had to leave for work with the issue still unresolved.

So, when I got to work, all wound up about this issue I'd been arguing about, while on the air I made an impassioned plea for my side of the argument. Then it was out of my system, and I forgot about it.

When I got home, the first thing Mary said was, "You were right."

I shook my head. "About what?"

"That thing we were arguing about this morning. I realized, you were right."

"Okay," I shrugged, then, out of curiosity, I asked, "What made you change your mind?"

"Well, Mary admitted, "I heard it on the radio."

"On the radio?" I asked. "What were you listening to? Wasn't it WAOC?"

"Well, yes," she agreed.

I laughed. "But, Mary," I said, "that was me!"

She looked surprised a moment, then said, "Well, I know. But it just sounded more logical when I heard it."

For the rest of the time I worked there, I had no arguments with Mary. Instead, I would simply announce my position on the air. When I got home, she'd be in agreement.

As I mentioned, WAOC went off the air about 5:30 pm—actually, at sunset. This was not unusual for AM radio stations in those days (though a midnight shut down was more common). On Fridays, I always got off work early because Wayne would do the final news of the day, and then call a friend of his on the air and spend five minutes talking about fishing. This was the only time Wayne was on the air that he spoke with his normal, Alabama accent. On the log, this was called "The Fishin' Show With Jake Garrett".

Since I am not a fishing person, I never consciously listened to these exchanges though I was aware of them. But one Friday, as I was growing increasingly nervous because Wayne hadn't yet arrived to take over, Wayne called…from Jacksonville, an hour away! "Flat tire," he said. "You're going to have to do the news…and the Fishin' Show." He then proceeded to tell me how to connect the telephone to the mixing board so I could share my Fishin' conversation on the air.

By this time Mary had arrived to take me home. I had her sit in the guest booth, since there were chairs in there, while I did the "patching" required to get the telephone working. Then during the commercial, I dialed Jake at the Lighthouse Pier and explained that I, and not Wayne, would be conversing with him.

Since Wayne used his accent for the Fishin' Show With Jake Garrett I decided, I would, too.

I don't really have a Southern drawl. A Florida accent is less pronounced; Besides, I lived my first seven years in New Jersey and then a few in Vermont. Nevertheless, a generic Deep South accent is the only one I can do well. So when Jake answered the phone, I said, "Howdee, Jake! Ah'm Paul Cilwa, sittin' in fer Wayne Sims, an' we gonna talk 'bout fishin'."

Jake proceeded to tell me (and the audience) how terrific the fishing was that day, how he'd caught several buckets of "blue-gill snout" or some such, and how with the weather so terrific he expected the fishing to be just as good tomorrow!

And that filled exactly one of the alotted five minutes.

Having no idea what else Wayne normally said to fill the time, I blathered for a moment and then queried, "Jake, ya know ah've bin list'ning to this here show week after week and ah've always wondered—whut do yew do with all them there fish? Ah mean, those blue-gilled snout things ya just caught, buckets of 'em—are ya gonna eat 'em, or sell 'em, or whut?"

"Wahl, Paul," Jake replied. "O' course, Ah do eat some of 'em. But mostly, Ah jes' give 'em away to folks whut don't have th' opportunity to fish for theyselves."

At that, I got a crazy idea. I loved the job at the radio station, but the fact was I made $1.60 an hour and didn't have much money. Mary and I were getting food stamps and they did help out, but they didn't go far. I didn't really like to eat fish—but here was free food that had essentially fallen into my lap.

I took a deep breath. "Well, ya know, Jake," I said, hesitantly, "Ah work in this here radio station an' Ah don't have time to fish for mah self…"

"Well," Jake interrupted, "come on down! Come rat up here to Lighthouse Pier an' Ah'll give ya three buckets of blue-gilled snout! Jes' come rat up!"

At this point, Mary was looking at me through the glass window of the guest booth as if I'd grown an extra head.

The Fishin' Show With Jake Garrett over, I played the Star Spangled Banner and shut down the transmitter and lights and locked the door behind us. "What were you thinking?" Mary demanded as we got into the car. I explained my reasoning as we drove across the Bridge of Lions to Anastasia Island where Lighthouse Pier was located.

When we got there, I knocked on the door until Jake answered. I decided to retain my Southern drawl so he wouldn't think I'd been making fun of him on the air. "Howdy, Jake!" I said. "Ah'm Paul from th' radio station."

"Good to meet ya, Paul!" he returned. "There's them buckets of blue-gilled snout rat over there. Do ya have a scaler?"

"Uh…" I wasn't sure what a "scaler" was. Something to weigh the fish with?

"Here, yew kin use mahn." And he handed me a sort of dull knife. "I'll turn th' lights on up at th' pier an' ya kin jes' clean 'em good so's yew kin take 'em home."

So I gingerly picked up one of the buckets and Mary followed me to the pier.

"Apparently we're supposed to clean these before we take them home," I explained.

"Have you ever done that?" she asked.

"No. You?"

"No!"

I swallowed. "Well, how hard can it be? This knife is called a 'scaler' so I guess we just use it to scrape the scales off."

"Where are you going to do that?"

"On the railing of the pier, I guess. See, there's bits of scales already there…and fish meat…and a little blood, I think."

By this time Mary, who was five months pregnant, was ready to hurl over said railing. "How are you going to pick the fish up?" she asked. "'Cause I'm not going to do it!"

"Um…" I thought about it. "I guess I'll just stab the top one with the scaler and flip it over here." I reached in with the blade, when the fish at the top of the pile did the unthinkable. It twitched. I jumped back, and Mary and I both screamed.

"It's alive!" Mary cried. "Can't we just throw them back in the water?"

"Now, calm down," I ordered. "It can't be very alive. Jake said he caught these this mornin'. I mean, 'morning'. They've got to be at death's door by now. If we throw them in the water, they might still be floating here in the morning and if Jake sees them he'll know we threw out these perfectly good fish instead of eating them."

"Then what are you going to do? You can't skin fish that are still alive!"

"No," I agreed. "Okay, I've got an idea." I returned to Jake's door and knocked again. When he answered, I handed him the scaler and said, "Ya know, the 'squitoes are bitin'. Mary's father has a scaler, so we're gonna jes' go to his house an' clean the fish there."

"Don't blame ya none," Jake agreed. "Jes' leave the buckets where ya found 'em after ya' git them blue-gills in yer cooler." And he closed the door.

We didn't have a cooler.

But thanks to Mary's pregnancy, we did have a pillowcase in the trunk of the car, left over from her first trimester when she was getting carsick. So Mary held the pillowcase open while I tumped the buckets over, pouring the fish from each into it. The survivors caused the pillowcase to throb and sway as if there was a live baby in it. I tied the end in a knot and put it back into the trunk.

On the way home, Mary kept asking, "What are you going to do with them? 'Cause I'm not eating those fish. No way."

But I had an idea. "What we'll do is this," I said. "We'll stretch Saran Wrap across the entire kitchen table. Then we'll let one fish at a time out of the pillowcase. I can wrap it in Saran Wrap and then neither of us will have to actually touch it while we put it in the freezer."

"But they're alive!" Mary protested.

"Yes, some of them might be. But they'll freeze to death in the freezer. It will be a peaceful death, just like going to sleep. And then when they're frozen and dead, we can clean them and cook them. Or give them away. Something."

So we got home and created a Saran Wrap table cloth. I then held the thrashing pillowcase carefully over the center of the table and tried to release one fish.

They all came out at once, mostly, on the table, flopping and gasping. Mary and I screamed and ran into the living room.

After a few minutes of listening to diminishing flops from the kitchen, I admitted, "I had no idea they were that alive. We could have thrown them back into the ocean after all."

"I'm not picking them up," Mary reminded me. "I'm five months pregnant."

"I know, I know." Suddenly I snapped my fingers. "Mary Joan!"

"Your sister?"

"She used to dissect fish when we were teenagers. She won't mind cleaning them!"

So we drove over to Mary Joan's apartment and explained the whole story to her. She stared at me. "I don't like to touch fish! Eew!"

"You used to!"

"That was years ago."

"It's still more experience than I've got," I pointed out. "Come on, you've got to help. You're our only hope!"

So we drove Mary Joan to our apartment. When I opened the door, I discovered the fish had done their best to throw themselves back into the ocean. So far, they'd made it into the hallway, our bedroom, the living room, and, of course, every corner of the kitchen. (In the morning we discovered one in the shower.)

Mary and I hid outside like the craven cowards we were, as Mary Joan located and gathered the fish, wrapped them in Saran Wrap, and put them in our freezer. Then, with some degree of disgust, she went back home.

Mary got rid of the fish in the shower the next day with a dustpan.

The blue-gilled snouts sat in our freezer for weeks. We could have thrown them out at any time; but I just couldn't bring myself to dispose of perfectly good food, especially when so much effort had been expended in bringing it home.

Finally, one day I bumped into our neighbor Tommy and he remarked that he really liked to eat fish. I immediately told him that we had a dozen or so blue-gilled snout things in our freezer, to which he would be more than welcome. He accepted them gratefully.

The next thing we heard, he and his wife had been hospitalized with food poisoning. Apparently it's really important to clean fish before freezing them.

It was three decades before I tried eating fish again.