| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/19/2024 Occurred: 4/27/1959 |

Page Views: 6757 | |

| Topics: #Vermont #Autobiography | |||

| The return to our house in Vermont after my father's death. | |||

In April of 1959, my newly-widowed mother bought a Ford Country Squire station wagon, took my sisters and me out of our Bloomfield, New Jersey, school and returned us to the property in Victory, Vermont, that we had left when my father took sick.

By April, Bloomfield's snow had melted. The same was not true in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. The fields and meadows were laid out in great swaths of white, like a Norse god's formal dinner table. As we reached the unpaved section of the River Road that connected North Concord and Victory, it was clear not even the sturdy Country Squire was going to be able to traverse twenty miles of mud to the house. And so Mom turned around and rented a room in the nearest town of size, St. Johnsbury, to await the break of spring.

The room we rented was in the Victorian-era home of Don and Sally Mullaley, whom Mom said were cousins of hers. However, she got Don's wife's name wrong, telling us it was "Molly." That was a misperception that I didn't get cleared up for fifteen years.

There were several rooms available for rent there, but ours was the only one actually rented. It contained two antique, high double beds. I shared one with Mom and my sisters shared the other. The room was crowded, not only by the four of us but also by the massive antique furniture. In addition to the beds, were two high dressers, bedside tables with Tiffany lamps, and framed prints from the 1930s. All the wood, including the trim and the door, was dark, almost black, reflecting ghostly images in varnish that had would have been applied when my grandparents were young.

On a high shelf was a television set, almost as old as the rest of the furniture. The only thing I remember watching on it was the movie Topper Returns, a comic ghost story. It was the first time I remember seeing clever special effects. I especially recall the footsteps of ghostly Joan Blondell "appearing" in the sand (to the consternation of Eddie "Rochester" Anderson). Mom also had to explain the concept of TV show spin-offs of hit movies, since I was already a fan of the Topper TV show.

We rarely left the room. Mom cooked our meals on a portable burner. The rest of the house was spooky, with more of the dark, musty furniture piled into every available corner. And outside, most days were cold and damp and muddy.

One evening Mom told me she had bad news. She'd been talking to the people who had taken in my dog, Sniffy, and the girls' dog, Rover, for the winter. Both animals had died, she said, of distemper.

I hadn't cried when my father died, but I was bereft at the death of Sniffy. Finally Mom told me that Sniffy had a daughter, and when we returned to our house in Victory, I could have the puppy.

Early Spring

It was a bright day a few weeks later when Mom made a second attempt to cross Victory Basin and get to our house. This time we succeeded. There was still snow on the ground, but the road had been graded and was dry enough to make it passable. Only the pines were green; the deciduous trees had not yet spouted their new coats of leaves although many of the branches looked ready to bud. The air was brisk, catching in the throat if one tried to breathe too quickly or too deeply. Happy to be outside, my sisters and I ran on the crisp snow, breaking through the glassy surface to the softer fluff beneath.

Inside, the house was very cold. Mom lit the kerosene heater in the dining room and we continued to wear our heavy coats inside. Our beds were still neatly made from when we'd left, the winter having left our sheets with a brittle smell that wasn't exactly musty but wasn't quite fresh, either. By nighttime the house was slightly warmer than before, but not very; and slipping between the sheets took a real effort of will, even in flannel pajamas.

In the morning Mom got us up for breakfast, urging us to hurry for school. She must have advised Mrs. Carpenter we'd be there, because shortly after we ate, Mrs. Carpenter's Volkswagen microbus climbed up the driveway and we got in. All the kids in the vehicle had colds, their noses running and dripping onto their scarves. The trip into town was long and jouncy.

I was happy to see Mrs. McGinnis, my second-grade teacher, again. She didn't ask about my father or anything else; just accepted me into her class as if nothing had happened, as if I hadn't even been away for months.

We settled into a routine that got us back from school each afternoon sometime around four.

Wrags

True to Mom's promise, on April 8, my birthday, we drove a short way down River Road to the Covey's, a family related somehow to the folks from whom we had bought the house to begin with. They had a pretty black, white and brown dog that looked a lot like Sniffy, with a clutch of bouncing little puppies. One of them spotted me and came running; when I picked her up she licked my face and wriggled so that I could hardly hold her.

I named her "Wrags."

And I was very definite about that spelling. My intention was to combine the concepts of "wags" (the way she wriggled her whole body) and her rag-like appearance.

Wrags spent the summer outside. She wasn't "fixed" and she'd had no shots. I was instructed to keep her tied to the garage for three days so she would "learn this is home." Afterwards, she ran free, often returning late in the afternoon covered in burrs or soaking wet. Once she came back whimpering, a fistful of porcupine quills stuck into her face. We had to use a pair of pliers to remove them.

But I hugged her, and fed her and she licked my tears away when things went wrong. She ran and played with us, and no one was happier than she when we returned home at the end of a school day.

Renovations

My dad's purpose in buying this property was to turn it into a hunting and fishing lodge on what he hoped would be Victory Lake. That lake didn't yet exist but would be created if the Victory Dam project succeeded. Politics and early environmental efforts were blocking the dam; but our house still might become a hunting lodge if it were made attractive enough. As it was, though, the house was barely habitable even for my sisters and me. It was frigid and inaccessible in winter, hot in summer (though not unbearably so), had no electricity other than that provided by a small gasoline generator, and no reliable running water. If we were to be able to take in sportsmen, we would need a lot of modernization. Thus the Renovation.

This was a major construction job. The house had been built sometime around 1860, making it a century old. The surface issues of cold and no electricity lay far above more serious, structural problems. The plaster walls were crumbling, held together only by paint and flaking wallpaper; the outer clapboard walls were rotting and the roof leaked in too many places to count. While Mom didn't actually do the work, she hired the people who did and assigned the jobs. She was, thus, the contractor.

First, the place had to be made livable. She replaced the kerosene heater with a more modern gas heater that put out a lot more warmth. And she bought a propane gas-operated electric generator, which powered a water pump that gave us actual pressurized water, which in turn made the toilet work correctly and made baths possible. The wood/kerosene/gas stove was replaced by a more modern gas range. The gas refrigerator, however, we kept, as it worked properly even though it wouldn't keep ice cream frozen solid; an electric refrigerator would have drawn more current than the generator could produce.

Our gas needs were supplied by a large propane gas tank placed near the west end of the house. A truck came by each month during the summer to check the level and top it off.

Mom hired her cousin, Cyril Brown, to do the renovations. Cyril brought with him a friend, Raymond Larabie, to assist. Cousin Cyril was about Mom's age, but Ray was much younger, 30, tops. He was also tall and quite handsome, in that Brylcreem sort of way. Eventually, Cyril went home to his wife in New Hampshire, citing health issues; but Ray stayed on, sleeping in the room adjacent to mine, on the antique rope bed that had one leg cut off, its stump resting on a step at the door.

When school let out for the summer I spent my time watching Cyril and Ray work. I was fascinated by the renovation. On the outside of the house, the men methodically removed all the rotted boards, replacing them with new, then painted the whole thing a light blue grey, with white trim on the windows, doors, and four corners of the building. Ray replaced the roof, too; fortunately the frame supporting it was still solid but all the old shingles came down, replaced by new ones made of tarpaper covered with new, blue, sparkly sheets. The house could be seen just as a car got off the last of the three "narrow" bridges, about a quarter mile down the road. Freshly painted, the house was transformed from mustard-colored eyesore to a jewel sparkling on the hillside in the summer sun.

Possibly the most useful addition was a screened-in front porch, built around the door to the kitchen. It made the side of the house that was most visible to the road look more like a front; and when the mosquitoes were particularly bad, we kids could play there and still be, sort of, outside.

Inside, the plaster was removed in most rooms and replaced with the newly-popular sheet rock—but not before wiring was installed in every room to support electrical outlets, switches, and ceiling lamps. Another cousin, Ken Brown, took down the gas chandelier from the dining room, wired it, and put it up as an elaborate electrical ceiling light in the living room. Atop the sheet rock Ray and Cyril pasted wallpaper. Mom let my sisters and me select the wallpaper for our own rooms. Mary Joan and Louise chose a paper with a green tint and lots of leaves; I selected a design with blue flowers on an elaborately twisted vine.

The solid wood floors were painted battleship grey, roughly the same color as the exterior walls; the baseboards and door and window trim were painted white.

A couple of local "boys," as Mom called them, removed the collapsed lumber

from what was once a large barn; she then had them tear down the smaller barn

once occupied by Nanny the Goat and the chicken coop. (Mom had sold the

livestock the previous fall.) Mom

then

selected un-rotted boards from all this and had Ray build a complete set of

kitchen cabinets out of the "weathered pine." Because Mom was short (only

4-foot-eight) she had the counters built about three inches lower than the

standard, which made them convenient for her—and me—but difficult for any

visitors to use.

then

selected un-rotted boards from all this and had Ray build a complete set of

kitchen cabinets out of the "weathered pine." Because Mom was short (only

4-foot-eight) she had the counters built about three inches lower than the

standard, which made them convenient for her—and me—but difficult for any

visitors to use.

Best of all, the water tank was removed from my room; the water pump, located in the basement, had a tank of its own.

Lights In The Woods

Because "the grid" had not yet come to our remote bit of wilderness, there were no street lights, or lights of any other kind. So the nights were dark as being in a blanket; not even the stars were brilliant enough to light the way on a moonless night.

I remember us pulling into the driveway one night. Cousin Cyril, who drove us, and my mother, had seen a "funny light" near the house which they announced was the reflection of our car lights in the eyes of a wild animal. We sat quietly in the car for (it seemed like) an hour before my two younger sisters and I quietly got out of the car and filed into the house and went to bed. We were a rambunctious bunch; we never did anything quietly. But we did that night, and looking back it strikes me as odd behavior.

Disappearance

Nanny and the calves usually hung out around the house, where there was plenty of tall grass and bushes. But once in awhile Nanny would get a jones for exploring. Usually she would head north up the dirt road towards Gallup Mills, a small community at a crossroads about an eighth of a mile up, with the calves close behind her. Mom and Joan and Louise and I would walk there and, sure enough, there they'd be somewhere along the road, enjoying the taste of other bushes growing on the side.

One day my sister, Joan, six at the time, turned up missing. We looked everywhere for her, but she was nowhere to be found—certainly not in the house, and not in the usual play places around it, either. Mom and Louise and I got the idea she might have wandered to Gallup's Mills. We walked there and back, my mother becoming more and more frantic as we failed to see any sign of her. Mom had always warned us that we might be kidnapped (I have no idea where that idea came from) and she was at a loss as to what to do. When we got back to the house, she sat at the dining room table, put her head down and started sobbing hysterically. Louise and I tried desperately to calm her down. Louise decided to get a cushion from the living room for Mom's head—and found Joan, deep asleep on the sofa. It took several minutes to rouse her. She swore she'd been sleeping there all the time.

At The Window

One night I got out of bed and went to the top of the stairs. My mother and sisters were standing in silence at the foot of the stairs, staring out the window. I joined them and asked what they were looking at. "The Northern Lights," my mother replied, and I looked, but I couldn't see anything. Finally I went back to bed, leaving them standing fixed at the window in silence. They no longer have any memory of the incident at all.

Electricity

One of the very cool aspects of all this was the automation. The generator turned itself on automatically whenever someone activated any electrical device that drew 60 watts or more. So all our lamps contained 60-watt light bulbs. My electric phonograph only drew 40 watts; so if I wanted to play it, I had to turn on my room light first, then the record-player.

Likewise, the water pump turned itself on whenever the amount of water in the tank dropped below a certain level; and since the pump drew more than 60 watts, that would automatically turn on the generator (if it wasn't already running). The end result was that the generator only ran occasionally during the day, pretty much all evening, and rarely during the night. It was also located at the far end of the house, beneath the "woodshed", so we could barely hear it when it was generating.

Now that we had electricity, we could run the TV set that had been waiting patiently through the previous year. We only had "rabbit ears" (tabletop antennae), but since we lived on the side of a mountain we got fairly good reception from the one station in the area. It was Channel 7, which was affiliated with the new ABC television network.

The only time the TV picture failed was when the pump was running. The generator must not have produced enough power for the pump and the TV both. Like most people, when a commercial came on, we would all run for the bathroom and flush the toilet. That used just enough water to turn on the pump, which would then make the picture on the TV flutter so badly we'd miss the next minute or two of program. We finally had to create a house rule that made it okay to not flush until after we'd turned the TV off for the night.

Midnight Invasion

Once, while we were watching TV, the generator suddenly just stopped. Our house lights had been off anyway, but the TV flickered off to black. Mom lit a couple of candles but, with nothing else to do and no ability to fix the thing in the dark, we decided to just go to bed.

Late that night, Mom was awakened by voices from downstairs. "You get the silverware," someone said. There was a bluish, flickering light downstairs—from the burglars' flashlights, she thought. Ray and Cyril were gone on one of their weekends home. Mom slept with a pistol at her bedside and loaded it in the dark, thinking that these crooks must have destroyed the generator just to put us at a disadvantage. The two intruders—she could make out two voices—continued to itemize their ill-gotten gains as she tiptoed down the stairs. She could see from the glow of their flashlights that they were in the living room—which was odd, because, other than the TV set, there really wasn't anything in the living room anyone could take or would want—and the TV set was a big, heavy, bulky unit that wouldn't be easy to steal.

Taking a deep breath, she burst into the living room, pistol leveled, ready to blow the brains out of anyone who would invade her home. However, there was no one there. The generator had, apparently recovered on its own (perhaps a heat-related problem?); and, since we had never turned the TV off, the potential power draw instantly started the generator back up. Mom had been eavesdropping on burglars in some movie on the Late, Late Show.

Photography

This was the year I was given permission to take photos with the family Brownie, a 127-format camera. Mom showed me how to load it with film, which was usually Kodak Verichrome Pan though sometimes Mom would buy Ansco black and white film if the price was better. Each roll of film could take 12 square photographs. The film cost about a dollar a roll, and the processing and prints added another dollar or two to the price.

I had never encountered the concept of "documentary" but that was the kind of pictures I took. I loved the landscape around our property: Miles Mountain to the south, the pine forest hillside to the north, the meadows to the east and the river on the west. I took many pictures of the house; I photographed the visitors who came and went. Soon I was the family photographer; the Brownie was kept in my room.

I got an allowance of 25 cents a week. This wasn't quite enough to keep me in film. I took an old cigar box, and a small cash-register-shaped coin bank, taping one to the other to create a "film bank" where I could store both unprocessed rolls of film and save money for the processing. It so happened that my dad's sisters, Aunt Al and Aunt Lou, were visiting at the time so I ran down to show Aunt Lou (my favorite) what I had made. Aunt Lou, of course, made an immediate and sizable donation—probably five dollars in change! It had not occurred to me this would happen and I was startled, but grateful. And, afterwards, whenever someone came to visit, I would graciously show them my Film Bank…just in case.

From then on, I always had enough money for film and processing.

Superman's Other Secret Identity

Just about all the gay guys I know, experimented with wearing women's clothing when they were little, though often for unlikely reasons. (That is, it wasn't always to pretend they were girls.) I was no exception. I loved to play Superman and had, with Mom's help, made a super-suit out of underwear, a towel, fishing boots, and a red 'S' drawn on a napkin-folded-into-a-triangle and Scotch-taped to my T-shirt. I would run around the house, arms outstretched; and since our property was our own, private park, I would run around outside dressed that way as well.

Part of playing Superman is being Clark Kent. But there were no suitably-sized men's business clothes to wear: no hats, no jackets, no ties. Mom had given away all my father's clothes soon after his death; and they would have been much too big for me, anyway. But it was the concept of a secret identity I found interesting, anyway, more than any specific secret identity. Besides, I thought Lois Lane was pretty dumb for not being able to see through that disguise.

It occurred to me a far more effective disguise—one no one would ever expect—would be as a woman. And so I came up with the idea of "Suzie Darrin", Superman's double-secret identity.

What gave me the idea was a costume that Mom had in her truck. The "costume" was probably a perfectly normal party or cocktail dress from the 1930s, hopelessly out of date by 1959, all purple satin with sequins and beadwork. It came with matching high heels, and a hat with more sequins and a purple veil. It must have been quite the outfit in its day

With Mom's permission, I put the outfit on. As Mom was so short, the outfit fit me pretty well. Granted, I had no boobs; but rolled-up socks adequately filled the gown's bodice. The shoes didn't fit me at all, and I gave up wearing them pretty quickly. However, I did try putting on lipstick.

Ray, the carpenter, was not comfortable with this game. He took me aside one day to explain to me that boys who wore girls' clothes were called "queer" by other boys, and sometimes beat up for no other reason. I was not accustomed to having my style of play criticized, and was embarrassed and humiliated. But, as I told Ray, there were no other boys on our property; and no one else would know unless he told someone. Within the context of what an eight-year-old is supposed to know, there was no other objection Ray could make.

So, for the rest of the summer, Suzie Darrin made regular, if sporadic, appearances on the property. However, she was never seen at the same time as Superman. Do you suppose that she and he could be the same…?

Nah. Of course not.

Late Summer

All in all, it was a great summer. We kids had stretches of property we could wander at will, with no one telling us it was dangerous or to be careful. For us kids, the house was safe and the grounds around it, an extension of that. Blueberries, blackberries, and raspberries were abundant. Although once in awhile someone might suggest we "pick" berries to bring home (that would be Aunt Al, who visited once or twice and who took seriously the adage that idle hands are the devil's playground), we mostly just grazed when we felt like it.

Part of the plan was to put up electric fences around the pastures, though we no longer had any livestock. (But we might get some!) So we had a pile of fence posts. We also had a long ladder that Ray used for getting onto the roof. I figured out how to balance the ladder on the pile of posts, making a very long seesaw. I also found that it could be balanced in such a way that both Louise and Mary Joan could perch on one end, while I balanced them on the other, making my invention a seesaw for three. We literally spent hours on it. When I went to bed, I felt like I was still seesawing; I could hardly get to sleep.

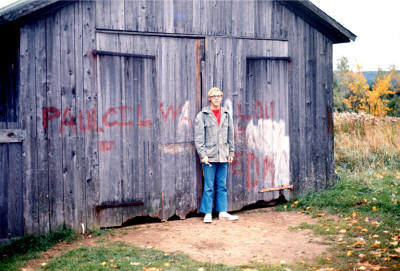

Me visiting the garage in 1969.

My dad had originally planned to paint the house barn red; and to that end, he had bought (at auction) four cans of barn-red paint. That would not have been enough to paint a two-story house, of course. But the paint was there in the garage (a small outbuilding) and I found it. Before anyone could stop me, I had painted my entire bicycle, wheels, handlebars, chain, seat and all. That ruined the bicycle, of course, though I had outgrown it anyway and besides it wasn't much use on our property where there were no paved surfaces. I also painted my name on the door of the garage. When I made a return trip in 1969 it was still there; and it remained, faintly, throughout the seventies until finally new owners tore the building down.

Accident

It was on one of our frequent visits to St. Johnsbury that we kids were permitted to buy some soda pop. There was a pop dispenser in the department store, and I was given the change and authority to dispense from it. I eagerly bought a root beer, and so did little Louise. But Mary Joan got an orange soda, and I immediately regretted my choice. Orange soda sounded so much better than root beer! Why hadn't I thought of that myself?

I made the best of my drink, watching enviously as Mary Joan nursed her orange soda, making it last through the ride home to Victory, and then, and then! storing the remainder in the refrigerator.

Other things distracted me the rest of the evening. And I'd forgotten it by morning, when I decided to boil myself an egg for breakfast.

I was allowed to do that. Most days we just had cereal and milk, but sometimes, especially on weekends or summer days when there was more time, I was permitted to boil water, add an egg or two, wait the required five minutes, then carefully pour the scalding water down the sink and eat the eggs.

I obtained the saucepan, filled it with water, and carried it across the room to the stove, which I lit and stood back while it got hot enough to boil. I had recently learned that "a watched pot never boils" so I was careful not to look at it. Instead, I went to the refrigerator for the egg. And there it was: Mary Joan's leftover soda.

She wasn't around. I was certain she had forgotten about it. There was hardly enough left to drink anyway. If she'd really wanted it, she'd have drunk it yesterday. If I were to drink it, I'd certainly appreciate it more than she. And then there'd be the empty bottle, which she could turn in for two pennies. She couldn't turn it in if it weren't empty. By drinking it now, I would be doing her a favor.

I drank it, no more than two swallows. It was wonderful. The world was brighter and my mouth was happy. I put the egg into the now boiling water, the empty bottle under the sink with the others waiting to be turned in, and waited.

Just as the five minutes ended, Mary Joan came into the room in her pajamas—I was still wearing mine, as well—and opened the refrigerator door. I lifted the heavy pan of still-boiling water and turned to begin the careful walk across the kitchen to the sink, intent on not spilling any of it.

"WHO TOOK MY ORANGE SODA?" Mary Joan bellowed, her voice amazingly stentorian for coming from such a tiny body. I said nothing, partly because I was still intent on making it across the kitchen, and partly because the answer would only make her angrier.

"YOU DID, DIDN'T YOU?" she demanded, and rammed me with her left shoulder, an interception that could've taken down a professional fullback. The pan of boiling water tilted and poured boiling water over Mary Joan's left arm and my right leg. We both screamed. The pan crashed to the floor. I don't know what happened to the egg.

Adults immediately converged on us: Mom, Ray, and a carpenter named Pete who'd been working at the house for a week or two. Someone removed my pajama bottoms, embarrassing but even I, at eight years old, knew it was necessary. Mom concentrated on Mary Joan, asking her what happened. "HE STOLE MY SODA!!!" was her explanation.

I had never experienced such pain. The front of my leg was red and raw. Skin hung from it like cobwebs. Someone ran for butter to rub on it, a useless folk treatment of the era. Fortunately, none was found. Soon we were bundled into the car and jounced over the rough road to St. Johnsbury, location of the nearest hospital. Back then the emergency room was also the lobby. I don't remember waiting long but the whole experience is, admittedly, fuzzy. When we were seen, ointments and bandages were applied. We were given no pain medication because, as Doctor Dixon put it, "children can't feel pain; they just think they do."

That night it was hard to sleep. I normally slept on my stomach but the pressure on the front of my leg was too painful. Each day the dressing had to be changed, and that hurt like heck. But my leg did heal, eventually; in my case without a scar, though Mary Joan still has marks on her arm that she associates with this incident.

In any case, I've never stolen anyone's soda since. And when I must cart boiling water from the stove to the sink, I still insist that everyone else leave the kitchen.