| By: Paul S. Cilwa | Viewed: 4/25/2024 Occurred: 6/1/1958 |

Page Views: 9594 | |

| Topics: #Vermont #Victory #Autobiography | |||

| Rural life in the 1950s. | |||

| Milestone: | Change of Residence |

|---|---|

| Address: | 1291 River Road, Victory, Vermont |

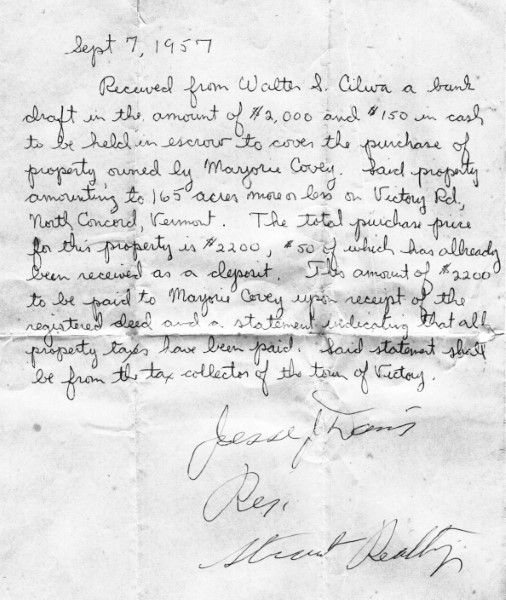

In 1957, my parents made a purchase without consulting me.

My folks waited until school was out for the summer, then packed all our stuff into an open-framed trailer, and us into the Studebaker; turned the house over to the family who had rented it from us, and headed North to a century-old house in Victory, Vermont. At 7, I had no idea where Vermont was or even what it was, much less why we were going. All questions were answered with, "You'll see."

It was a long trip, and we'd gotten a late start and Dad had to nurse the car which slowed us further. We finally arrived in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom very early in the morning. I awoke after Dad had turned off Vermont's Route 2 onto the dirt road to the township of Victory. The road followed the Moose River, crossing it several times so that the river was sometimes on the right side of the car, and sometimes on the left; most times, obscured anyway by the thick pines that lined the road and continued, unbroken, up the mountain slopes.

What surprised me most, though—besides the fact that the road was unpaved—was a type of fog I'd never seen before, and haven't seen since. It consisted of rolls of fog, tubes of fog, draped out along the valleys and hillsides like giant pipes.

After some 25 miles of road, we arrived at our destination: An old, mustard yellow, two-storey house on the side of a hill, looking over the road with a kind of forlorn pride, like the elderly king of a small principality sitting on his front stoop waiting for petitioners who never come.

The driveway up the slope to the house was, if possible, in worse shape than the dirt road. The owners of the house seemed to be expecting us and showed us through the place. I don't remember much from that first visit, just the huge wood stove in the kitchen, kerosene oil lamps in each room, and an organ that Mom called a "melodeon" in the hallway. My littler sister, five-year-old Louise, found she could (barely) reach the pedals that pumped the thing and play a few notes.

The house had no electricity, because Victory had not yet been wired for it. It also wasn't connected to the national telephone lines. (Some houses had access to the "fire line" telephone, a single line shared by all homes that used it. But this was not one of them.)

Apparently the adults reached an agreement unknown to us kids, because Mom and Dad agreed to buy the place from the current owners, the Hoveys. The agreement included 65 acres of property, the house, the wood stove and the melodeon, and various pieces of furniture including tables and beds.

Moving Day

The Hoveys must have been anxious—and ready—to move. It was just a few weeks later that we towed a small, open trailer with all our portable stuff, like dishes and our television set and sheets and blankets. We did not bring furniture because the house we were moving into was already furnished, as was our old house, which we were renting.

The trip was made long before the creation of the Interstate Highway System; it was "side roads" all the way. Some of them were pretty steep. Dad had to stop the car at the crest of one hill to let it cool, and we got out to stretch our legs just in time to see the last dish fall from the open trailer and follow its fellows rolling on edge down the hill.

Good old Melmac dishes—unbreakable, you know.

When we arrived at the end of that washboard road, and entered our new house—Mom was not pleased. The Hoveys had stripped it. Not only were the tables and beds gone, so was the wood stove and the melodeon. All that was left in the place was a slightly wobbly three-legged stool and, on it, a chipped coffee cup with a quarter cup of cold coffee inside.

The air outside was swarming with tiny gnats we learned later are called "no-see-ums". Louise promptly got bit by one; her neck swelled to the size of a cantaloupe and Dad had to rush her into town to a doctor, thinking she'd got the mumps.

We had to retreat and spend that night in a motel.

The next day Mom and Dad bought furniture, paying extra to have at least some of it delivered that day. Dad never bought anything new. He usually haunted auctions and what today are called "garage sales" for usable cast-offs. But our mattresses were new, as was the sofa. There was no hope, however, of finding a new kitchen range that would run on wood or kerosene. He found a used model that would burn wood, kerosene, or bottled gas. Although decades old, it was still sturdy as an Egyptian monument, because that's how they used to build things.

The Kitchen

The kitchen was the heart of the house. When we moved in, there were two rooms: A small eating room (too small to be called a dining room) and an adjacent cooking room. Dad and Tommy Westinberger, his son-in-law, took out the intervening wall within a few days of our arrival. They also removed a great barrel of flour that had been built under a cabinet and was hinged so that it could be swung out or in as needed. I hated to see that go, as it looked like a lot of potential fun.

We had the wood, kerosene or gas-burning "cook stove" where the original stove had been, so eight-inch exhaust pipes could be connected to the chimney. (The house had no fireplace, but it had two chimneys nevertheless for wood stove exhaust.) At first we cooked using the kerosene, until Dad could get a tank of bottled gas delivered and filled; then Mom cooked on the gas jets by preference. However, the oven only heated by kerosene or wood. I don't remember Mom ever using it.

There was a sink in the kitchen with no drain, resting beneath a hand-operated water pump. Usually such pumps are atop pipes that reach into a spring or well. But ours drew water up from a cistern in the basement. When you wanted to empty the sink, you simply lifted it out of its base, took it to an open window, and poured its contents outside.

The basement was dirt-floored with walls made of granite blocks. It was always cool, even on the hottest, most humid summer days. But we didn't play down there much, because there were lots of spider webs (and, presumably, spiders) and things that made little noises in the farthest, darkest corners. The stair that led to the basement came from the kitchen, and even at the top of the stairs it was cool. Some former owner had mounted a wooden box with a single shelf onto the wall inside the landing, to serve as a place for milk and other perishable foods. We used that as our "ice box" (sans ice) until Dad got a bargain on a gas-operated refrigerator.

Water poured into the basement cistern from a lead (!) pipe that emerged from the wall. We'd been told the pipe, nearly a century in use, was buried and led to a spring located somewhere in the pine forest that stopped just short of the back of the house.

The gas refrigerator was a wonder. It ran on the same bottled gas as the gas jets in the stove, yet in the refrigerator things got cold instead of hot. I spent years wondering how the thing worked.

One day Mom and Dad took my sisters into town and left me in Tommy's care. Tommy promptly fell asleep on the sofa, and I decided to make myself some pancakes. At seven, this was not something I had ever done and I was excited and frightened by the possibility. But there was leftover pancake batter in the refrigerator, and I could think of no reason why I shouldn't make myself a snack. I successfully struck a match and lit one of the gas jets, then set out to find a frying pan. I couldn't locate one, but I did find the pot of a pressure cooker whose lid had long been lost. Mom usually used it to make spaghetti, but I saw no reason not to make pancakes in it. I put it on the burner and poured a perfect pancake into its bottom, then tried to locate a spatula. I couldn't find that, either, and had to settle on a knife.

The ingredient I had missed, of course, was shortening. By the time I tried to peel the pancake off the bottom of the ungreased pan with the knife, it had burnt solid into the cookware. It wouldn't budge. Sadly, and a little guiltily, I turned off the burner and left the mess for Mom to find.

When they got home, of course, it was Tommy who got yelled at, not me. But the experience encouraged Mom to teach me to cook, with (as it turned out the next year) disastrous consequences.

The House

Here's the layout of the house. It was built as a long, narrow box; and, even though the broad side of it presented to the road, the front door was actually on one of the narrow faces. That door led into a foyer, with a stairway leading upstairs on the right, and a hall leading to the rest of the first floor on the left. The melodeon, now gone, had rested against the outer wall at the foot of the stairway. There was a Harry Potter-style enclosed closet beneath the stairs.

The hallway led into the dining room, or at least that's what we called it. Mom put her nice dining room table and chairs there, anyway, pulled out of our house in New Jersey when the renters didn't work out. (They'd been there just a few weeks when my father went down unexpectedly and caught them selling our furniture.) We also had a gas space heater installed there.

The house, which must once have been quite a luxury place, was piped for gas lights. There were gas light fixtures in the walls, and a beautiful gas chandelier hanging in the dining room. However, these lamps wouldn't use bottled gas and were never connected. (We later found some kind of tank buried in back of the house containing some powdered chemicals that had, apparently, generated the gas for the lamps. But by then they'd been removed.)

The dining room had doors to three other rooms. As you stood in the door from the hallway, at the other end of the same wall to your right was the door to a first-floor bedroom that Dad eventually made into an inside bathroom. (I still remember how difficult it was for him and Tommy to get the iron bathtub he'd bought at auction down the hallway, which wasn't quite wide enough for it.) In the wall to the right was the door to the kitchen, and on the left was the door to the living room.

The living room also had a door into the hall, and a table on which sat our big, heavy, useless TV set.

There was a whole section to the house beyond the kitchen. This part, in today's terms, would be called "unfinished." On the first floor, this section had enough floor space and windows to create four or six rooms of the size of others in the house, but instead it was open and had been used as a workroom by the former owners. We called it the "woodshed," though we never stored any wood in there. We kids didn't go in there often.

If you took the front stairs to the second floor, on the way you'd notice the beautiful wood banister. It was unfinished and worn, but we later sanded and varnished it and it was quite lovely.

The banister continued past the top of the stairs, wrapping around back on itself to protect walkers on the extended second floor landing from falling. In the very front of the house, over the front door, was a very small room that Mom used as the "sick room." If one of us kids got sick, she would have us sleep there instead of in our own beds. I have no idea why.

Next was the largest bedroom, which Mom and Dad took. It actually had a small closet, which excited Mom because, she said, at the time the house had been built, few homes had closets at all. But that closet dovetailed with one that opened into the next room, in which my sisters slept. It was also large, and doubled as a playroom. Both Mom and Dad's bedroom and the girls' room had grates in the floor, through which heat from downstairs could rise in the winters. We kids quickly discovered that the entire unit could be removed, leaving a hole through which we could drop things to the first floor. To put an end to this, Mom passed on the cautionary tale of my father who, when he was young, was spying on his sisters from his bedroom grate. He quietly removed the grate, then dropped the family cat on the head of his sister, my Aunt Louise, which startled her so much she dropped an expensive platter she was holding. Dad, of course, was punished. So we must never drop things through grates.

That didn't stop us from spying through the grates, though. However, there was no one for us to spy on but the adults; and their conversations were stupifyingly boring. So we didn't actually do it much.

My room came next; it's door was in line with the stairs. Dad didn't want us to have to rely on the cistern in the basement and a hand pump; in order to get the bathtub to work, we would have to have running water. He calculated that the spring on the hill was higher in altitude than my bedroom, and eventually put a water tank in it. The tank would fill, however slowly, and then "gravity flow" would let the water come out the taps in the bathroom and fill the inside toilet. However, we apparently didn't have quite enough gravity, as the water dribbled out of the taps and took some 45 minutes to fill the toilet tank.

In addition to my bed and dresser, I also had a small cuckoo clock in my room. My window faced pine trees standing at attention in the back of the house, and with no electricity in our house or anywhere else in the township, nights were very dark. However, I wasn't afraid of the dark, so I didn't mind. And even today, I prefer sleeping where it's dark and the only light comes from ten thousand stars.

The house had been built in two sections. The older section had lower ceilings than the new section. The dining and living rooms, and the bedrooms I've just described, were in the "new" section; the kitchen and woodshed were in the "old" section. Through my bedroom was a door to another bedroom, which was down two steps from mine. It was a small room, and no one made a bed short enough to fit against any of the room's walls. However, in an outbuilding we found an ancient bed frame with one leg sawed short. I suggested we use that. Mom had her doubts, but it turned out the frame fit so perfectly in that room it was clear the leg had been sawed off for just that purpose, supported by one of the steps. The bed had no slats, just holes. We had to string rope through the holes to hold a mattress. Mom said that, once, all beds had ropes instead of slats.

I believe a large part of my awareness that time is a continuity comes from my exposure, at that young age, to how things had changed within my mother's lifetime. I knew that the differences between the house in Vermont and the house in New Jersey, like electricity and gas and rope slats, were differences of chronology, not location.

So the rope bed room was outfitted and declared a "guest room."

That room also had a door into another room, a slightly larger one that faced the broad front-side of the house, with a view of the road and the glimmer of water flickering through the trees from the Moose River. It was also made into a guest bedroom, though anyone who stayed in it would have to pass through the rope bed room to get to it.

The final door in the rope bed room opened onto a steep, narrow, New England "back stairway." Those stairs took you down into the kitchen. But if, instead of going downstairs, you stepped across the landing you'd find yourself in the second-floor expanse of the unfinished section. We called this room the "First Attic" because it had been used as one; there were still some ancient trunks there the Hoveys hadn't taken with them. We used this room as our primary playroom. My Dad got me a cabinet Victrola and a chest of 78-rpm records to play on it and we kept it there.

But, for awhile at least, there was a lot of traffic through the First Attic because, on the outer, "back" wall of the house (the official back, narrow end) was an innovation—an outhouse that wasn't truly outside. It was a lean-to tacked onto that side of the house, its foundation level with the cellar but continuing past the first floor and ending on the third with not one, not two, but three holes for people to poop in. There was a big hole, a middle-sized hole, and a little hole. Dad used the big hole; Mom and I fit the middle one, and the girls used the little one. So high above its base, there was no smell and while it did get rather close in the summer and was plagued by flies, still it added a certain familial camaraderie to the basic toilet function.

Above the First Attic, and accessible by a steep stairway in it, was the Second Attic. This space, under the roof, was a true attic. However the floor wasn't completed and it was dangerous without being any fun, so we didn't really use it. But if you followed it toward the narrow front of the house, and went up the two steps that led to the "new" section, you found yourself in the Third Attic, which also contained an old trunk and which had a nicely finished floor and a window that overlooked the yard and the fields and mountains beyond. I loved the Third Attic, and wanted to remodel it into a duplicate of Jor-El's laboratory from the comics. (Jor-El was Superman's Kryptonian father.) I had no resources to do such a thing, but I spent endless hours making plans on paper, most of which ignored realities of scale and would have crowded dozens of rooms into the tiny space.

Commuting

The house's mustard yellow color, on close inspection, turned out to be the result of decades of paint and neglect revealing bits of color from each face-lift the place had received. Apparently it had never been painted the same color twice. And the interior walls were covered in faded, peeling wallpaper. Plans were made to repaper them.

But Dad couldn't spend the whole week with us. He still had his job at Bendix, in New Jersey, where he was an engineer. He was in his fifties but not yet ready to retire. In fact, it was just a few months ago I learned that it had been Mom's idea to move to Vermont, not his. He hadn't even wanted to go, since his four sisters and their families all lived in New Jersey, as well as his son and daughters from a previous marriage. But Mom's happiest childhood and teenaged days had been spent in Vermont, and she apparently did her passive-aggressive best to convince Dad to move us there.

So Dad would make the drive to New Jersey on Sunday night to make it to work on time Monday morning, and return home to Vermont very late Friday night (or early Saturday morning) where he was expected to continue renovating the house.

Relatives

A parade of relatives came through. Aunt Al, Dad's oldest sister, showed up with her husband, Uncle Frank. Aunt Al was a fierce taskmaster who firmly believed the Devil resided in idle hands and that an idle child was up to no good. So, even though it was Summer, there was no playtime while Aunt Al was there. She also had some unusual nutritional opinions which she imposed on everyone else. My sisters still remember her forcing them to eat raw eggs, which was presented as a nutritional supplement, rather than a meal. I didn't eat them, because I wouldn't. No amount of force could make me open my mouth if I didn't want to, which Aunt Al eventually learned. Mom, always cowed by strong women, neither objected nor assisted; and so I won that round, at least.

Aunt Al had no children of her own.

Aunt Rose was the next sister down (Dad was the middle child of five) and she and Uncle Mike came to visit. They did have kids and so were much more fun to be around.

Aunt Lou was just a year younger than Dad, still single and the scandal of the family because she lived with a man who'd been unable to get a divorce from his wife, who'd been committed to a mental institution. I didn't like Uncle Wally's cigars, but I did like him; and I adored Aunt Lou. She had been Dad's favorite sister, too.

And finally came Aunt Gene, whose husband was also an Uncle Mike. They had one son, a little older than me but I don't remember his accompanying them in 1958.

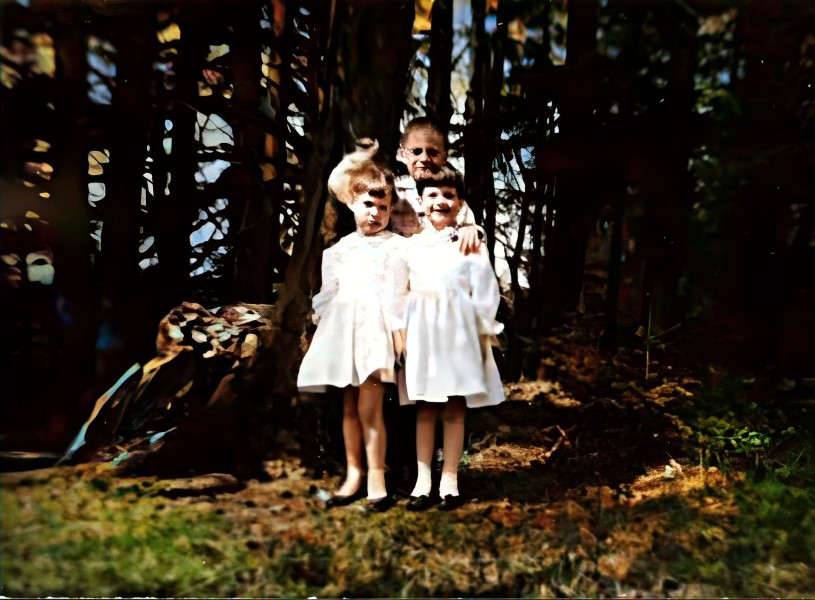

Mom's best friend, whom we called Aunt Bernie, came with her husband Uncle Bob and his son, Robbie Junior. Robbie Junior was about 14, and afflicted with a degenerative spinal disorder that would someday confine him to bed for the rest of his life. But in 1958 he could still walk, if a bit unsteadily, and he and I roamed the area around the house.

Outdoors Cuisine

In addition to the house itself, there were four outbuildings. One was a chicken coop. Another was the size of a very generous two-car garage, and we called it the Garage. However, we never put a vehicle in there because it was full of stuff, most of it unidentifiable and all of it old. There was a small barn behind the house, the pines crowding it on two sides, and the remains of a larger barn that had collapsed some years earlier. Mom kept us away from the ruins by warning us that rats probably lived in them.

Near the small barn, on a pile of what we'd been told was "manure" (but no one defined) grew stalks of a reddish-green plant. When we brought them in to Mom, she declared them to be rhubarb and good to eat, like celery, with salt. It would be 15 years before I discovered that rhubarb is also used in pies. But I loved the tart, salty taste and munched on it almost every time I went outside.

The specialty of the house, however, was blueberries. They grew everywhere, but especially on the broad expanse between the house and the road that we called the "front lawn." Dad decided to name our property "Blueberry Hill," after the song which was popular then. I would lie down for hours, the sun shining on my face through the branches of a blueberry bush, reaching up and plucking berry after berry to eat.

The driveway degenerated from ruts in the ground to wagon tracks in the tall grass past our house, as it continued into the woods and up the hillside. We rarely ventured far along that road but along its sides were red and black raspberries and blackberries, as many as we could eat. When Aunt Al visited, she insisted that we pick berries (that was one of our "chores") and put them in a bucket to bring home, where she would pour milk and sugar on them, which was supposed to make them taste better. But my sisters and I preferred them straight from the bush, and surely ate far more than ever made it into our buckets, with giggled mutual promises to never tell that we'd eaten the produce.

Pets

Dad had bought the property with the idea that he would turn it into a lakeside hunting lodge. Now, that would seem difficult considering there was no lake. But the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was planning to dam the Moose River and flood the Victory Bog (also known as the Victory Basin). Local environmentalists protested the plan, as Victory Basin is a unique ecological area containing Vermont's largest boreal forest, and an enormous amount of wildlife. The hunters Dad wanted to lodge would have had little to hunt if the dam had gone through.

In 1967 the Victory Basin Wildlife Management Association purchased the Victory Basin from the New England Power Company, ending the dam plans. But in 1958, the possibility was still very much in the air. And in the meantime, Dad decided we may as well farm the land, starting with a few cows, a goat, and some barnyard pets.

First came the dogs. They must have been obtained over Mom's objections, because she'd always been terrified of dogs. Sniffy, who was such a perfect example of "mongrel" that in my dog book, the picture of a mongrel looked just like him, became mine. A fat little beagle was to be shared between my 6-year-old sister, Joan, and 5-year-old Louise. Joan was a little vague about the whole pet-naming ritual. When Dad said she could name the dog, she asked what he meant.

"You can call him whatever you want," he explained. "Like Fido or Rover."

She went with "Rover."

Dad shored up the weak spots of the chicken coop and made it the home of two rabbits. I named mine Whitey. Joan named hers Jumpy-Over-The-Mountains. Our younger sister, Louise, was considered at five to be too young to have pets, or at least that was the justification for buying two and "giving" them to the oldest two kids.

I'm not sure what Dad had in mind for those rabbits' ultimate fate, though I'm pretty sure it was not to eventually retire in some Old Pets Home. But whatever it was, the dogs had a different idea. They found the rabbits irresistible. And in spite of any common sense, the rabbits seemed to want to get out of the chicken coop as badly as the dogs wanted them to. We usually caught them first, and then would locate and patch the hole they'd escaped through.

One morning Louise looked out her bedroom window and noticed a couple of bits of white stuff on the driveway. Because we were so far out into the country that there was absolutely no litter anywhere, it stood out. "Mommy!" she yelled. "There's some Kleenex on the driveway!" Louise always had a very firm sense of where things should be.

But when Mom returned from her investigation, she was ashen and wouldn't let us go out to look. "It's the rabbits," she said. "The dogs got them."

I wanted to point out that this wasn't so much the dogs' fault as it was the rabbits', who clearly had no sense at all. But Mom seemed too upset. This only proved to her what evil creatures dogs were.

In any case, the chicken coop couldn't be wasted, and Dad promptly replaced the rabbits with three ducks.

The ducks also got out of the coop on occasion, but the dogs seemed quite disinterested in them. Mom would instruct me to run and gather them up; the biggest one was the size of a five-pound bag of sugar and it wasn't easy to pick up if it didn't want to be. But I managed to get them and put them back into the coop.

I also got to feed them. I loved this part. Mom would make them some kind of mush and put it in an aluminum pie plate. I would crawl through the little door in the coop and place the plate onto the ground. The ducks definitely knew what was going on; they would crowd me until I backed away, sticking their bills into the mush and making little quacks of pleasure as they inhaled their meal.

But the biggest additions to the family were the calves and goat.

Apparently it's cheaper to buy a baby calf and let it grow, than to buy a full-grown cow whose milk is immediately available. Dad bought two, Brownie and Blackie. At the same time, he brought home Nanny, the goat.

Nanny had a definite and distinct personality. Actually, she reminded me a lot of Aunt Al. Nanny immediately adopted the calves, who followed her everywhere. Now, calves eat grass and say "Moo" and goats eat leaves and say "Bah." But Brownie and Blackie ate leaves and said "Mah!" That's how into their adopted mother they were.

Nanny was very curious and was fascinated about the big building her humans went into. One day I came in and forgot to close the door. Suddenly I heard Mom screaming, "The goat's in the house! The goat's in the house!" She didn't seem to have any idea what to do about it. Little Louise didn't hesitate. She marched right up to the goat, stuck her index finger in Nanny's face, and barked, "Back, Nanny! Back!" Nanny backed right out of the house and into the yard. From then on, she would do anything Louise told her.

But Nanny couldn't abide weakness, and she had no mercy for Mom, who she could sense was afraid of her. One day Mom was in the yard, raking, when she put down her rake, tines up, to pick up a rock. Nanny saw how the rake was arranged and practically ran to it, jumping onto the tines with her front hooves so the handle went flying, smacking Mom in the butt.

Milk

Nanny had a special power. She gave milk. She had two great teats (we called them "handles") and when you grabbed one and squeezed, milk came out. I was occasionally given the task of milking her, half-filling a bucket each time. I was initially afraid it would hurt her, but she seemed to enjoy it, standing patiently until I had gotten all there was to get.

But there was no way I was going to drink that stuff!

I mean, it was all well and good to call the white stuff "milk" but, at seven, I was quite aware that milk came from the milkman or the grocery store, in glass or waxed cardboard cartons. There was no way I was going to drink anything that came out of a goat's handles.

Nanny liked to eat blueberries, just as I did. And when she ate a lot of them, there would be a blue streak in her milk. In raspberry season, there'd be a red streak; and in blackberry season a dark purple one. I've had people in years since tell me this doesn't happen, but I saw it with my own eyes.

And then came the day I caught Mom transferring milk I had drawn from the bucket to a used milk carton.

"What are you doing?" I demanded. I was furious that she would consider trying to trick me, and I told her so.

"But I've been doing it for weeks," she said, "and you never noticed."

Well. I was still annoyed, but I couldn't argue with the result. Raw goat's milk did taste like "real" milk. So Mom threw out the used carton and I drank goat's milk from a pitcher for the rest of the time we lived there. I suppose I could point out this incident as being the first time I realized that, what was on a label, didn't necessarily reflect the contents.

Lights In The Woods

Because "the grid" had not yet come to our remote bit of wilderness, there were no street lights, or lights of any other kind. So the nights were dark as being in a blanket; not even the stars were brilliant enough to light the way on a moonless night.

I remember us pulling into the driveway one night. The cousin who drove us, and my mother, had seen a "funny light" near the house which they announced was the reflection of our car lights in the eyes of a wild animal. We sat quietly in the car for (it seemed like) an hour before my two younger sisters and I quietly got out of the car and filed into the house and went to bed. We were a rambunctious bunch; we never did anything quietly. But we did that night, and looking back it strikes me as odd behavior.

Disappearance

Nanny and the calves usually hung out around the house, where there was plenty of tall grass and bushes. But once in awhile Nanny would get a jones for exploring. Usually she would head north up the dirt road towards Gallup Mills, a small community at a crossroads about an eighth of a mile up, with the calves close behind her. Mom and Joan and Louise and I would walk there and, sure enough, there they'd be somewhere along the road, enjoying the taste of other bushes growing on the side.

One day my sister, Joan, six at the time, turned up missing. We looked everywhere for her, but she was nowhere to be found—certainly not in the house, and not in the usual play places around it, either. Mom and Louise and I got the idea she might have wandered to Gallup's Mills. We walked there and back, my mother becoming more and more frantic as we failed to see any sign of her. Mom had always warned us that we might be kidnapped (I have no idea where that idea came from) and she was at a loss as to what to do. When we got back to the house, she sat at the dining room table, put her head down and started sobbing hysterically. Louise and I tried desperately to calm her down. Louise decided to get a cushion from the living room for Mom's head—and found Joan, deep asleep on the sofa. It took several minutes to rouse her. She swore she'd been sleeping there all the time.

At The Window

One night I got out of bed and went to the top of the stairs. My mother and sisters were standing in silence at the foot of the stairs, staring out the window. I joined them and asked what they were looking at. "The Northern Lights," my mother replied, and I looked, but I couldn't see anything. Finally I went back to bed, leaving them standing fixed at the window in silence. They no longer have any memory of the incident at all.

The Lost Spring

Before Dad put the water tank in my room, every now and then the water from the hillside spring would inexplicably stop flowing into the basement cistern. Mom and I would then have to get it going again.

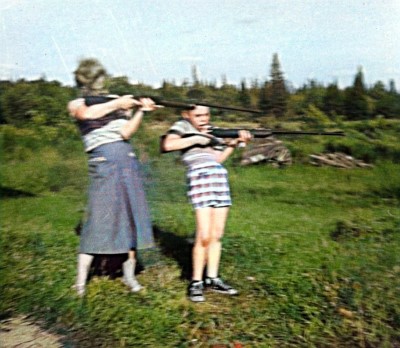

To do so, we'd have to find it, first. Looking back, I cannot believe that Mom left two little girls alone while we went spring-hunting, but she did. Unaware that they should be upset about this, they would simply continue playing with their dolls and dollhouses while Mom and I put on sturdy clothes, got our rifles, and headed into the woods.

Yes, Mom taught me to shoot when I was seven years old. I was pretty good at it, too. She would put one of the old, broken coffee cups the Hoveys had left on top of a fence post some fifty yards away, and before long I could reliably hit and shatter it, even though I had to hold the weapon with the barrel under my armpit, since my arm wasn't long enough for my finger to reach the trigger if I held the rifle properly.

So, knowing there were bears in the woods, Mom and I would set out with these .22 gauge rifles, confident in our belief that if we did encounter a bear along the way, we could safely dispatch it without danger to ourselves.

We would set out along the wagon road that continued up the mountain from our driveway, Mom keeping a sharp eye out for trails into the woods on our left. There were many of them, most or all of them animal trails, of course. But one would trigger some kind of memory and I would follow Mom from the sunlight into the cool, still pine forest.

That part of the woods was quite overgrown. Sniffy and Rover would also accompany us (and probably kept us far safer from bears than those rifles ever could), barking and dashing about. They would run off and we could here them crashing about through the underbrush; then, just when we'd suspected we'd los them, they would burst into view, check on us with their tails wagging and out of breath, then return to whatever scent had fascinated them so.

Eventually, inevitably, we would come upon the spring, leaves floating upon its surface, and blocking the ancient lead pipe sticking into its side. I would have to sit on a board that covered it, my boots in our drinking water, remove the leaves and then fasten the rubber hose of a remodeled bicycle pump we'd brought with us. A few pumps of the handle, and the gravity flow would be restored.

One time, Sniffy burst into the clearing when I was sitting on the board. He jumped joyfully onto my lap, which broke the board and sent us both into the cold water. (And now, a dog had been in our drinking water, but Mom never seemed to think this was significant and, of course, at seven I didn't know any better.)

It was the return back home that always seemed to take longer than the search for the spring. When I was grown, Mom always insisted that she knew where we were, that we were never lost. Maybe so, but I recall that at least two of these trips started in the morning, yet we didn't make it back home until dinner time.

On one of those occasions, we finally emerged from the woods into the farthest of a string of sand pits located on our property. So now we knew where we were, but had a long trudge before we finally got home. When we climbed the side of the last sand pit, putting us on the opposite side of the house from the driveway (along a steep, rutted way we called the "short driveway"), we spotted Joni and Louise talking to some stranger, who was standing outside his car.

Mom immediately fired her rifle into the air; the man flinched as if she'd hit him. She then began marching in his direction as he walked toward us. When he was within speaking distance, he said, "Do you greet all your visitors that way?" It turned out he was just an insurance agent, and had been asking the girls if he could speak to their parents. He may have changed professions after that.